文章编号:1004-0609(2011)07-1728-06

相转变过程对红土镍矿氯化离析的影响

李新海, 张琏鑫, 胡启阳, 王志兴

(中南大学 冶金科学与工程学院,长沙 410083)

摘 要:在氯化剂CaCl2·2H2O的加入量为原矿质量的8%(以氯计)、还原剂焦炭加入量为原矿质量的6%及升温速率为5 ℃/min的条件下,对菲律宾红土镍矿进行氯化离析;采用TG-DTA和XRD研究菲律宾红土镍矿氯化离析升温至1 000 ℃及冷却过程中的物相转变。结果表明:红土镍矿中的氧化亚铁在700 ℃开始进入蛇纹石中,形成富铁橄榄石相,破坏蛇纹石的晶格结构,提高镍的活性,有利于镍的氯化和离析;而氯化剂所释放的氯成为铁迁移的媒介;冷却过程中物相没有发生明显变化。当生料中Fe3O4的加入量为原矿的10%(质量分数)时,精矿中镍的品位达到13.14%,回收率达到80.12%,比未加Fe3O4时的回收率提高了约10%。

关键词:

中图分类号:TD95 文献标志码:A

Effect of phase transformation on

chloridizing segregation of laterite ores

LI Xin-hai, ZHANG Lian-xin, HU Qi-yang, WANG Zhi-xing

(School of Metallurgical Science and Engineering, Central South University, Changsha 410083, China)

Abstract: Under conditions of chlorinating agent dosage (CaCl2·2H2O) of 8% (vs mass of raw ore), reductant dosage of 6%(vs mass of raw ore) and heating rate of 5 ℃/min, the chloridizing segregation of nickel laterite ores from Philippines was carried out, and the phase transformation of chloridizing segregation of nickel laterite ores at temperatures up to1 000 ℃ and the phase reversibility with cooling were investigated by TG-DTA and XRD. The results show that the Fe-rich forsterite is formed with the ferrous oxide entering into the serpentine at 700 ℃. Therefore, the lattice structure of serpentine is failure, which is beneficial to chloridizing segregation, since the activity of Ni is enhanced, and the chlorine that is released from chlorinating agent acts as the medium of the transfer of iron. The phase is not changed obviously in the cooling process. When Fe3O4 adding in the raw materials is 10% (mass fraction), the grade in the concentrate of Ni reaches 13.14%, and the recovery achieves 80.12%, which increases by 10% compared with that without adding Fe3O4.

Key words: nickel laterite ores; chloridizing segregation; phase transformation; phase control

镍属于亲铁元素,地壳中镍含量0.008%(质量分数),居已知元素的第24位。在地壳中镍存在于红土镍矿和硫化镍矿中,另外,深海锰结核中也含有一定量的镍[1]。红土镍矿中镍占镍总量的70%。虽然目前硫化镍矿仍然是镍的主要来源,但是随着高品位硫化镍矿的减少,越来越多的人开始研究红土镍矿提取镍的工艺[2-3]。目前,制约红土镍矿发展的主要因素是工艺不成熟,红土镍矿的成分复杂、多变,对其基础理论研究比较匮乏。因此,对红土镍矿进行基础研究是必要的。

近年来,人们对红土镍矿的氯化离析过程进行了深入的研究。MA和PICKLES[4]及USLU等[5]研究红土镍矿的微波加热。LIU等[6]研究马弗炉加热过程中各种因素如焙烧温度、焙烧时间、氯化剂种类、氯化剂用量、还原剂种类和还原剂用量等对红土镍矿氯化离析的影响,但未对红土镍矿氯化离析过程的物相变化进行研究。尽管VALIX和CHEUNG[7]、LI等[8]及CHANG等[9]对红土镍矿在还原气氛中的物相变化进行了研究,且RHAMDHANI等[10-11]研究了红土镍矿在还原气氛下焙烧后产物的结构、物相变化及反应热力学,但对红土镍矿的氯化离析借鉴作用甚微,因为在氯化离析过程中,氯对铁和镍的迁移起着至关重要的作用。为此,本文作者采用TG-DTA和XRD技术,研究菲律宾红土镍矿氯化离析过程的物相变化和氯在铁、镍离析过程中的作用。加入添加剂,控制离析过程的物相变化,以取得最佳的离析效果。

1 实验

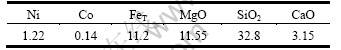

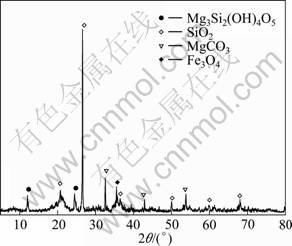

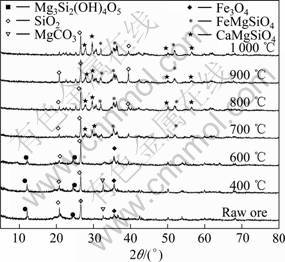

本实验所用红土镍矿为含有蛇纹石相和碳酸镁相的高硅、高镁、低铁红土镍矿,其化学成分见表1,XRD物相分析结果见图1。 原矿粒度为0.12~0.15 mm;氯化剂采用CaCl2·2H2O 用量为原矿质量的8%(以氯计);还原剂采用粒度为0.18~0.25 mm的焦炭,其用量为原矿质量的6%。

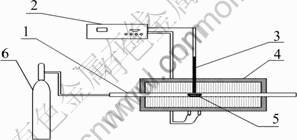

焙烧实验在如图2所示的管式炉中进行。氮气以0.1 L/min的流速流入管式炉。将矿粉、氯化剂和还原剂混合均匀,加入适量水造球得到球团直径为15~20 mm的生料。将生料放入烧舟后,再将烧舟放入管式炉中央,然后,以5 ℃/min的升温速率升至指定温度后,迅速取出水淬。对焙烧到不同温度的熟料进行XRD物相分析。

表1 红土镍矿的化学成分

Table 1 Chemical composition of nickel laterite ores (mass fraction, %)

图1 红土镍矿的XRD谱

Fig.1 XRD pattern of nickel laterite ores

图2 焙烧实验装置图

Fig.2 Schematic diagram of roasting equipment: 1—Corundum tube; 2—Temperature control instrument; 3—Thermocouple; 4—Electric heat furnace; 5—Porcelain combustion boat; 6—Nitrogen steel bottle

氯化离析实验所用氯化剂CaCl2·2H2O的加入量为原矿质量的8%(以氯计),还原剂焦炭的加入量为原矿质量的6%,加入添加剂和水混合均匀造球得到生料。以5 ℃/min升温速率将样品升温到1 000 ℃,在1 000 ℃恒温60 min,取出水淬湿磨过筛,粒度为0.038~0.048 mm;然后经0.3 T磁选得到精矿和尾矿。通过化学分析得到精矿和尾矿中镍的品位并计算回 收率。

2 结果与讨论

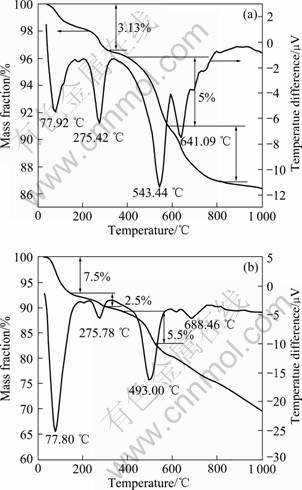

原矿及加入CaCl2·6H2O(以氯计,用量为原矿质量的8%)与焦炭(用量为原矿质量的6%)混合均匀生料的TG-DTA曲线如图3所示。由图3可见,原矿的DTA曲线在77.92、275.42、543.44和641.09 ℃处存在4个吸热峰。77.92 ℃处的吸收峰对应物理水的脱除;275.42 ℃处的吸收峰对应针铁矿化合水的脱除;543.44 ℃处的吸收峰源自碳酸镁的分解;641.09 ℃处的吸收峰是羟基硅酸镁脱水分解所致。生料由于以下两个反应:

CaCl2·6H2O=CaCl2·2H2O+4H2O (30~80 ℃) (1)

CaCl2·2H2O=CaCl2+2H2O (200~260 ℃) (2)

导致其DTA曲线上77.80 ℃与275.78 ℃处的峰与原矿的峰明显增强,而与其对应的TG曲线上质量损失也明显增加。原矿中在543.44 ℃碳酸镁的分解峰,而混合矿中在493.00 ℃就结束了,这主要是由于氯化钙的加入对碳酸镁的分解起到了一定的促进作用。

图3 原矿和生料的TG-DTA曲线

Fig.3 TG-DTA curves of raw ores(a) and raw materials(b)

在氮气保护气氛下,升温过程中红土镍矿在不同温度下的物相变化如图4所示。由图4可知,原矿的主要物相为石英、蛇纹石、磁铁矿和碳酸镁。当温度为400~600 ℃,碳酸镁分解;当温度为600~700 ℃时,蛇纹石相分解消失,形成富铁和富钙橄榄石相,这期间伴随着氯化钙的分解和Fe3O4的消失。随着温度的继续升高,含铁和钙的橄榄石相逐渐增多,晶形也更加完整,SiO2相的含量降低。但当温度升高到800~900 ℃时,低温石英相(三方)转变为高温石英相(六方)[12-13],造成SiO2相在2θ=20°和2θ=40°处峰值增高。

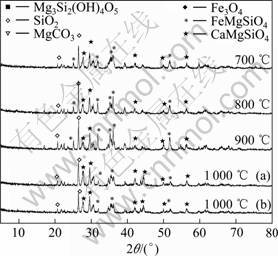

降温过程中红土镍矿在不同温度下的物相变化如图5所示。图5中分别为1 000 ℃(1 000 ℃,(a))、1 000 ℃恒温60 min(1 000 ℃,(b))及降温到900、800和700 ℃时熟料的XRD谱。从图5可以看出:在降温过程中,红土镍矿的矿相并没有发生明显改变,所以,红土镍矿氯化离析的过程是不可逆过程,在降温过程中物相是稳定的。但值得注意的是,必须控制降温过程的气氛为弱还原性气氛,防止镍铁合金高温氧化。

图4 升温过程中氯化离析红土镍矿的XRD谱

Fig.4 XRD patterns of chloridizing segregation of nickel laterite ores during temperature increase process

图5 降温过程中氯化离析红土镍矿的XRD谱

Fig.5 XRD patterns of chloridizing segregation of nickel laterite ores during temperature decrease process

虽然红土镍矿氯化离析的目标产物是镍,但是因为铁的活性比镍的高,矿石中铁含量是镍含量的10~30倍,因此,研究离析过程必须考虑铁的离析。从以上分析可知,铁对离析过程中熟料的物相变化起着重要的作用,反应方程式如下:

当焙烧温度低于560 ℃时,物相转变的相关反 应为

Mg3Si2(OH)4O5(s)=Mg3Si2O7(s)+2H2O(g) (3)

CaCl2(s) +H2O(g)+SiO2(s)=CaSiO3(s)+2HCl(g) (4)

CaCl2(s) +H2O(g)=CaO(s)+2HCl(g) (5)

Fe参与的反应为

Fe3O4(s)+8HCl(g)=FeCl2(s)+2FeCl3(s)+4H2O(g) (6)

2FeCl3(s)![]() 2FeCl3(g)

2FeCl3(g)![]() Fe2Cl6(g) (7)

Fe2Cl6(g) (7)

Fe2Cl6(g)+2H2O(g)=2FeOCl(s)+4HCl(g) (8)

6FeOCl(s)+3H2O(g)+CO(g)=2Fe3O4(s)+

6HCl(g)+CO2(g) (9)

当焙烧温度高于560 ℃,物相转变的相关反应为

Mg3Si2O7(s)+3FeO(s)+SiO2(s)=3(Mg,Fe)SiO4(s) (10)

Mg3Si2O7(s)+3CaO(s)+SiO2(s)=3(Mg,Ca)SiO4(s) (11)

Fe参与的反应为

FeCl2(g)+H2O(g)=FeO(s)+2HCl(g) (12)

Fe3O4(s)+CO(g)=3FeO(s)+CO2(g) (13)

在水蒸气气氛下,CaCl2在550 ℃与SiO2反应生成HCl[15],而羟基硅酸镁脱水,为后续铁的氯化与迁移提供水和氯化氢。虽然铁在低温反应过程中发生Fe3O4→ FeCl2 (FeCl3) →Fe3O4循环,但是,Fe3O4的位置发生了变化,向羟基硅酸镁附近迁移,且新生成的Fe3O4暴露在矿石表面,活性较高,更容易被还原成FeO,从而促进FeO与硅酸镁反应生成富铁橄榄石相。硅酸镁晶格的破坏提高了镶嵌在硅酸镁中镍的活性,有利于下一步的离析[14]。

通过上面实验及理论分析可知,在红土镍矿氯化离析过程中铁起着极为重要的作用,通过氧化亚铁与硅酸镁反应生成富铁橄榄石相而提高橄榄石相中镍的活性。为了提高低铁、高镁矿石镍精矿的品位和回收率,本文作者在红土镍矿中分别添加Fe3O4和Fe粉,控制氯化离析过程中的物相变化,以生成更多的富铁橄榄石。Fe3O4的加入量分别为原矿质量的0、5%、10%、15%、20% 和25%,铁粉的加入量分别为原矿质量的0、0.1%、0.2%、0.3%、0.4%、0.6%,0.8% 和1.0%。经过离析-磁选后镍的品位和回收率如图6 所示。

从图6可以看出:随着Fe3O4加入量从0增加到25%,精矿镍的品位先增加后降低,镍的回收率具有同样的规律,但是,回收率降低的幅度比较小。这主要是因为Fe3O4被氯化迁移后,被还原为氧化亚铁进入硅酸镁的晶格,使镍的活性增高,从而使蛇纹石中的难以氯化的镍具有一定的活性,故能被氯化离析磁选。但是,随着Fe3O4用量的增加,被还原出来的铁不断增加,与镍一起被磁选,所以,精矿镍的品位因铁的增加而降低,但是,精矿镍的回收率并没有明显的降低,因为回收率降低的主要原因是铁的增多使部分铁镍合金粘附在硅酸盐表面,而未被磁选。

图6 Fe3O4和Fe粉的加入量对镍的品位和回收率的影响

Fig.6 Effect of dosages of Fe3O4 (a) and Fe (b) powders on grade and recovery of Ni

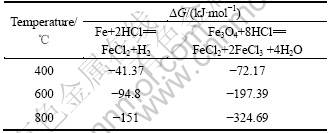

对比图6(a)和(b)发现,当Fe3O4加入的量为10%时,离析磁选后精矿中镍的品位为13.14%,镍的回收率达到最大值80.12%;而当Fe粉的加入量为0.2%时,离析磁选后精矿中镍的品位为19.21%,镍的回收率达到最大值76.23%。这是由于铁的氧化物更容易被氯化和迁移,对镍活性提高的促进作用更加显著。不同温度下Fe及Fe3O4与HCl气体反应的吉布斯自由能见 表2。

在原矿物料粒度为0.12~0.15 mm、氯化剂为氯化钙、氯化剂用量按氯计算为原矿质量的10%,还原剂焦炭用量为原矿质量的8%、粒度为0.18~0.25 mm,Fe3O4的加入量为原矿质量的10%,离析温度为1 000 ℃,离析时间为60 min,焙砂磁选粒度为0.038~0.048 mm、磁场强度为0.3 T的最佳条件下,所得红土镍精矿和尾矿的XRD谱如图7所示。从图7可以看出:精矿的主要物相为Fe、NiFe、(Mg0.39Fe0.52Ca0.09)SiO3和(Fe1.04Mg0.94)SiO4;尾矿的主要物相为SiO2、Fe、(Mg0.39Fe0.52Ca0.09)SiO3和(Fe1.04Mg0.94)SiO4。由于部分铁和镍铁合金与橄榄石粘附在一起,在球磨过程中没有剥离完全,因此,精矿中仍然含有非磁性的(Mg0.39Fe0.52Ca0.09)SiO3和(Fe1.04Mg0.94)SiO4。

表2 不同温度下Fe和Fe3O4与HCl气体反应的吉布斯自由能

Table 2 Gibbs free energies for reactions between Fe or Fe3O4 and HCl

图7 最优条件下红土镍精矿和尾矿的XRD谱

Fig.7 XRD patterns of nickel laterites concentrate(a) and tailing (b) under optimal conditions

3 结论

1) FeO在700 ℃开始进入硅酸镁相中形成富铁橄榄石相,硅酸镁原有的晶体结构被破坏,从而提高了镶嵌在硅酸镁晶格中镍的活性和可离析度。

2) 氯化剂CaCl2所释放的氯作为铁迁移的媒介,在氯化离析过程中促进FeO的迁移,从而促进FeO与硅酸镁反应生成富铁橄榄石相。

3) Fe3O4比Fe粉更容易氯化而发生迁移。当Fe3O4的加入量为原矿质量的10%时,氯化离析-磁选所得精矿中镍的品位为13.14%,镍的回收率为80.12%。相对于未加入Fe3O4氯化离析,镍的回收率提高了约10%。

REFERENCES

[1] LUO W, FENG Q M, OU L M, LU Y P,ZHANG G F. A comprehensive study of atmospheric pressure leaching of saprolitic laterites in acidic media [J]. Mineral Processing and Extractive Metallurgy, 2009, 118(2): 109-113.

[2] WEI L, QIMING F, LEMING O, GUOFAN Z, YIPING L. Fast dissolution of nickel from a lizardite-rich saprolitic laterite by sulphuric acid at atmospheric pressure[J]. Hydrometallurgy, 2008, 96(1/2): 171-175.

[3] ZHAI Yu-chun, MU Wen-ning, LIU Yan, XU Qian. A green rocess for recovering nickel from nickeliferous laterite ores[J]. Transactions of Nonferrous Metals Society of China, 2010, 20(1): 65-70.

[4] MA J, PICKLES C A. Microwave segregation process for nickeliferous silicate laterites[J]. Canadian Metallurgical Quarterly, 2003, 42(3): 313-325.

[5] USLU T, ATALAY U, AROL A I. Effect of microwave heating on magnetic separation of pyrite[J]. Colloids and Surfaces A: Physicochem Eng, 2003, 225: 161-167.

[6] LIU Wan-rong, LI Xin-hai, HU Qi-yang, WANG Zhi-xing, GU Ke-zhuan, LI Jin-hui, ZHANG Lian-xin. Pretreatment study on chloridizing segregation and magnetic separation of low-grade nickel laterites[J]. Transactions of Nonferrous Metals Society of China, 2010, 20(1): 82-86.

[7] VALIX M, CHEUNG W H. Study of phase transformation of laterites ores at high temperature [J]. Minerals Engineering, 2002, 15(8): 607-612.

[8] LI Jin-hui, LI Xin-hai, HU Qi-yang, WANG Zhi-xing, ZHOU You-yuan, ZHENG Jun-chao, LIU Wan-rong, LI Ling-jun. Effect of pre-roasting on leaching of laterite[J]. Hydrometallurgy, 2009, 99(1/2): 84-88.

[9] CHANG Yong-feng, ZHAI Xiu-jing, FU Yan, MA Lin-zhi, LI Bin-chuan, ZHANG Ting-an. Phase transformation in reductive roasting of laterite ore with microwave heating[J]. Transaction of Nonferrous Metals Society of China, 2008, 18(4): 969-973.

[10] RHAMDHANI M A, HAYES P C, JAK E. Nickel laterite (Part 1): Microstructure and phase characterizations during reduction roasting and leaching[J]. Transactions of the Institutions of Mining and Metallurgy, 2009, 118(3): 129-145.

[11] RHAMDHANI M A, HAYES P C, JAK E. Nickel laterite (Part 2): Thermodynamic analysis of phase characterizations during reduction roasting[J]. Transactions of the Institutions of Mining and Metallurgy, 2009, 118(3): 146-155.

[12] PICALES C A. Microwave heating behaviour of nickeliferous limonitic laterite ores [J]. Minerals Engineering, 2004, 17(6): 775-784.

[13] 周文戈, 谢鸿森, 赵志丹, 周 辉, 郭 捷. α-β石英相变的应变参数计算及其地质意义[J]. 高 压 物 理 学 报, 2002, 16(4): 241-248.

ZHOU Wen-ge, XIE Hong-sen, ZHAO Zhi-dan, ZHOU Hui, GUO Jie. Calculation of the strain, stress and elastic energy for α-β quartz transition and its geological significance[J]. Chinese Journal of High Pressure Physics, 2004, 16(4): 241-248.

[14] 张联盟, 黄学辉, 宋晓岚. 材料科学基础[M]. 武汉: 武汉理工大学出版社, 2004: 497-498.

ZHANG Lian-meng, HUANG Xue-hui, SONG Xiao-lan. Fundamentals of materials science[M]. Wuhan: Wuhan University of Technology Press, 2004: 497-498.

[15] ASAKI K H, KONDO Z. Hydrolysis of fused calcium chloride at high temperature[J]. Metall Trans B: Process Metall1, 1978, 9(3): 477-483.

(编辑 陈卫萍)

基金项目:国家重点基础研究发展计划资助项目(2007CB613607)

收稿日期:2010-06-18;修订日期:2010-07-29

通信作者:李新海,教授,博士;电话:0731-88836633;E-mail: lianxin-zhang@126.com