Oxidization mechanism in CaO-FeOx-SiO2 slag with high iron content

ZHANG Lin-nan(张林楠), ZHANG Li(张 力), WANG Ming-yu(王明玉), SUI Zhi-tong(隋智通)

(School of Materials and Metallurgy, Northeastern University, Shenyang 110004, China)

Abstract:

Oxidization mechanism in CaO-FeOx-SiO2 slag with high iron content was investigated by blowing oxygen into molten slag so as to oxidize Fe(Ⅱ). The relationship between Fe(Ⅱ) content and oxidizing time at different temperatures was obtained by chemical analysis. Microstructure of slag was observed by metallographic microscope and SEM. Phases compositions were ascertained by EDXS and XRD. Grain size and crystallizing quantity of magnetite(Fe3O4) were determined by image analyzer. The oxidizing kinetic equations were deduced. Confirmed by graphical construction method, Fe(Ⅱ) oxidizing reaction in CaO-FeOx-SiO2 slag system is of first order, and the reaction apparent energy Ea is 296.67kJ/mol in the pure oxygen and 340.30kJ/mol in air. The enrichment and crystal growth mechanism of magnetite(Fe3O4) phases were investigated. In oxidizing process, content of fayalite declines, while that of magnetite(Fe3O4) increases, and iron resources enrich into magnetite(Fe3O4) phase. All these provide a theoretical base for compressive utilizing of those slags.

Key words:

oxidizing; magnetite; kinetics; phase transformation; CaO-FeOx-SiO2 slag CLC number: TF811;

Document code: A

1 INTRODUCTION

CaO-FeOx-SiO2 slag system with high iron content plays important roles in various fields of metallurgy, and attracts more and more attentions with its gradually broader applications. Yazawa et al[1, 2] gave the oxygenate potential diagram in 1970s. Kaiura et al[3] used a rotating cylinder viscosity-meter to measure the viscosity at constant oxygen potentials. Some authors concluded that increasing Fe2O3/FeO ratio and p(O2) slightly decreases the viscosity of this slag[4-6]. Kongoli et al[7] confirmed that the increase of the viscosity at high oxygen potentials results from magnetite precipitation. Goel et al[8-10] assessed the Fe-O-SiO2 system, describing the liquid phase as a solution of the components of Fe, FeO, FeO3/2 and SiO2 by using binary interaction among all of them and mathematical description of the thermodynamic properties of the system. The effects of CaO, Al2O3 and MgO addition to silica saturated iron-silicate slag on copper solubility, Fe3+/Fe2+ ratio of the slag and the behavior of minor elements were investigated by Kim and Sohn[11]. Matousek[12] analyzed the phase transformation in FeOx-SiO2 system. LI et al[13] investigated the surface reaction between melting iron oxidation and CO-CO2 in both oxidization and reduction directions with TGA. However, research on the oxidization mechanism in CaO-FeOx-SiO2 slag with high iron content, especially the kinetics of those reactions, is rarely seen and there are still lots of ambiguity about phase transformation regularity in this slag system.

Based on the research above, the regularity of the phase transformation and the oxidizing kinetic equations of iron in the oxidizing process were studied in this work. Enrichment and crystal growth mechanism of magnetite(Fe3O4) phases were investigated, which provided a fundamental for compressive utilization of those slags.

2 EXPERIMENTAL

Synthetic slag was made by mixing chemically pure powders of iron, hematite, silica and calcium oxide in alumina crucible, heating in argon to 1380℃ and holding at this temperature for 1h. The crucible was taken out of furnace and the molten slag was immediately poured into water for rapid solidification. The chemical composition of the slag is listed in Table 1.

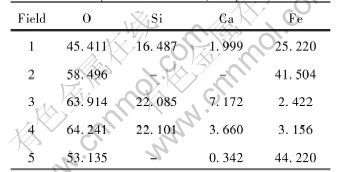

Table 1 Chemical composition of slag (mass fraction, %)

Two types of slag specimens were adopted: 1) slowly cooling specimen: after oxidizing for certain time, the molten slag was slowly cooled down for analyzing the valence status of iron cation and phase status in the slag; b) quenching specimen: the molten slag was rapidly cooled down by water so as to know the in-situ phase status and compositions.

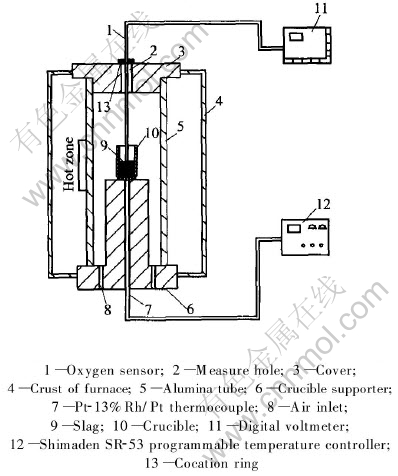

The main furnace used in this study was a vertical tube furnace with the maximum operating temperature of 1600℃, fitted with a programmable Shimaden SR-53 temperature controller. The furnace was heated with six vertical MoSi2 elements that were secured around the furnace work tube. The work tube was made of recrystallized alumina. Both ends of the tube were fitted with airtight metal plate assemblies that were water-cooled with a provision for gas inlet and outlet. Fig.1 shows the schematic drawing of the furnace setup. Oxidizing gas flow to the furnace was controlled and kept at 0.5L/min by glass rotor meter situated between furnace and gas supply cylinder. The crucible was made of recrystallized alumina with 10cm-high melting slag in it.

Fig.1 Schematic diagram of experimental setup

The contents of Fe(Ⅱ) in the slags were analyzed by ortho-phenanthroline redox titration, and that of TFe was determined by potassium dichromate volumetric method[14].

Slag samples were observed and assayed by metallographic microscope, SEM, XRD and EDXS to confirm the phase compositions. Grain size and crystallizing quantity of magnetite(Fe3O4) were determined by Quantimet 520 imagine analyzer.

3 RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

3.1 Oxidizing kinetics of iron in molten slag

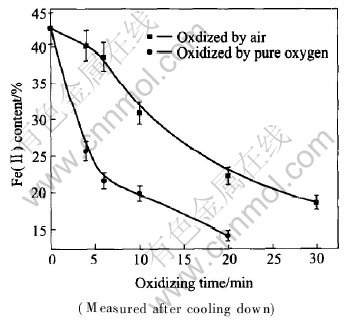

Fig.2 shows the relationship between content of Fe(Ⅱ)(mass fraction, %) and oxidizing time after cooling down in the atmosphere of air and pure oxygen in molten slags at 1573K. In air oxidizing process, Fe(Ⅱ) content declines with increasing oxidizing time. After 30min oxidization in air, Fe(Ⅱ) content is less than 18%; while using pure oxygen as oxidizing medium, after 20min oxidization, Fe(Ⅱ) content is less than 14.6%. Here, iron in slag mainly exists in the form of magnetite, in other words, most iron enters magnetite phase.

Fig.2 Relationship between Fe2+ content and oxidizing time

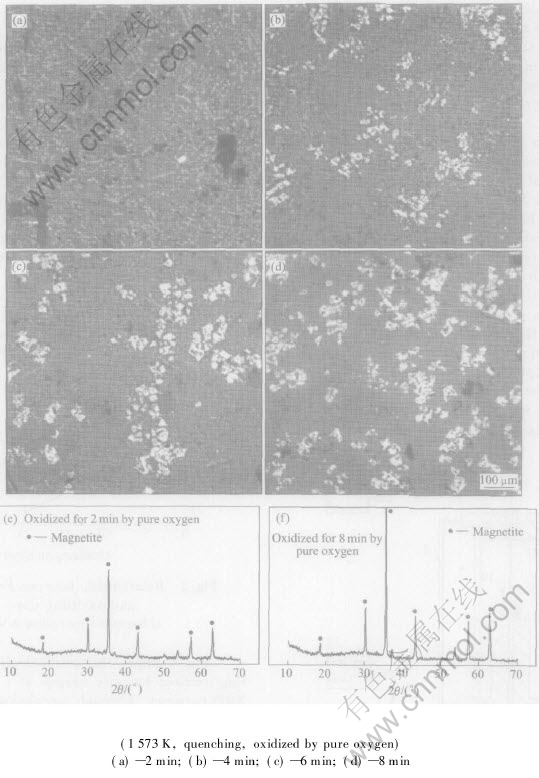

Fig.3 shows the morphologies of quenched slag oxidized by pure oxygen at 1573K and its XRD patterns. Through morphology of quenched samples of oxidized slags with different oxidizing times, we can clearly see that with increasing oxidizing time, the quantity of Fe3O4 increases, the melt becomes saturated, and Fe3O4 precipitates and grows up in size during the oxidizing process. The variety of the peak intensity and areas of XRD patterns of quenched slags confirms these trends and all these coincide with chemical analysis results shown in Fig.2 and Fig.4. It is also indicated that the variety of Fe(Ⅱ) content can be used to describe oxidization mechanism in CaO-FeOx-SiO2 slag.

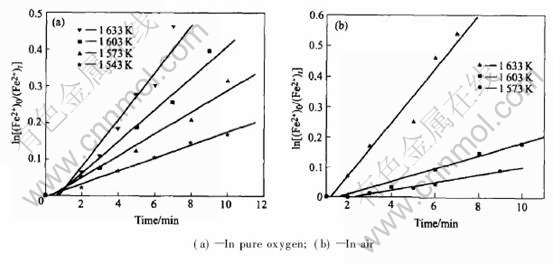

Fig.4 shows the relationship between ln[(Fe2+)0/(Fe2+)t ] and oxidizing time t(by pure oxygen and air). This figure shows nearly liner relationship between t and ln[(Fe2+)0/(Fe2+)t], which indicates that the oxidizing reaction is of first order. In those descriptions, (Fe2+)t is the mass concentration of Fe2+ at time t, (Fe2+)0 isthe mass concentration of Fe2+ at time t=0, and

Fig.3 Morphologies of slag and XRD patterns

Fig.4 Relationship between ln[(Fe2+)0/(Fe2+)t] and time of quenched sample

the slope of the line is reaction rate constant k.

The oxidizing reaction of Fe(Ⅱ) in slags is expressed by Eqn.(1):

4Fe2++O2(on interface)=2O2-+4Fe3+(1)

Reaction rate is as follows:

(Fe2+)t=(Fe2+)0-exp(-kt)(2)

Based on Arrhenius formula[15], from the relationship between ln(kFe) and 1/T, we get

lnkFe2+=-296672.5/RT+18.63(3)

lnkFe2+=-340300.9/RT+22.33(4)

Eqn.(3) is oxidizing kinetic equation of Fe(Ⅱ) in pure oxygen, with reaction apparent energy Ea being 296.67kJ/mol. And Eqn.(4) is oxidizing kinetic equation of Fe(Ⅱ) in air, with reaction apparent energy Ea being 340.30kJ/mol.

Values of apparent activation energy Ea may reflect mechanism of those oxidizing reactions. As we know, when Ea〈150kJ/mol, mass transfer is the controlling step; while Ea>400kJ/mol, surface chemical reaction is the controlling step and Ea can reach 418kJ/mol in some chemical reactions[16-18]. Based on the values of Ea and feature of the reaction rates, we may conclude that oxidization mechanism in CaO-FeOx-SiO2 slag with high iron content is a reaction mixedly controlled by mass transfer of the reaction constitutes and melting-gas surface oxidizing reaction.

3.2 Microstructure transformation mechanism in oxidizing process

Fig.5 shows the morphologies of slowly cooled

Fig.5 Morphologies of slowly cooled slags

slags. In oxidizing process, with the increase of Fe(Ⅲ) content and declining of Fe(Ⅱ) content, phase compositions change. Fig.5(a) shows the morphology of raw slags: bright phase is magnetite(Fe3O4); the other two phases are fayalite(Fe2SiO4, less bright) and olivine((Fe,Ca)SiO4, grey phase) and dark holes are air bubbles.

Figs.5(b) and (c) show the morphologies of slags oxidized by air for 5min and 20min, respectively. In oxidizing process, content of fayalite(Fe2SiO4) declines and that of magnetite(Fe3O4) increases. While after oxidized for 30min by air(Fig.3(d)), there is little fayalite in slags. The intensity and area variety of diffraction peak in Fig.6 shows the increasing of magnetite(Fe3O4) content and declining of fayalite(Fe2SiO4) content, which meets the case of the metallographic analysis in Fig.5.

Fig.6 XRD patterns of slowly cooled down slags

Table 2 summarizes the EDXS analysis results of the SEM in Fig.5. From the element compositions of the dark substrate phase(fields 3, 4), we confirm that it is a type of silicate solid solution of Fe and Ca, called olivine (Fe, Ca)SiO4, thus we get the phase constitutions of the slag mentioned above. From Table 2, we also realize that even magnetite(Fe3O4) is not strictly stoichiometric substance, and the atom ratio of O/Fe increases after oxidization.

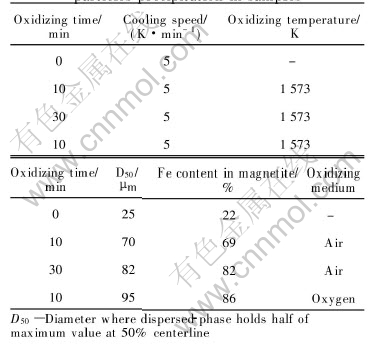

Table 3 lists the comparison of magnetite par- ticles precipitation in samples. By oxidizing, magnetite(Fe3O4) increases both in mass fraction and in crystal size after cooling down slowly. The average particle size is 80-95μm when cooling down at 5K/min, thus making it easily be separated from those waste slags.

Table 2 EDXS results of fields in Fig.4(molar fraction, %)

Table 3 Comparison of magnetite(Fe3O4) particles precipitation in samples

5 CONCLUSIONS

1) The Fe(Ⅱ) oxidizing reaction in CaO-FeOx-SiO2 slag system is of first order, with reaction apparent energy Ea being 296.67kJ/mol in pure oxygen, and Ea being 340.30kJ/mol in air.

2) Main phases in the slag after cooling is magnetite(Fe3O4), fayalite (Fe2SiO4), olivine((Fe, Ca)SiO4). In the oxidizing process, content of fayalite (Fe2SiO4) declines; while that of magnetite (Fe3O4) increases, which can achieve the aim of enriching iron resources into magnetite(Fe3O4) phase.

3) In the isothermal oxidizing process, Fe(Ⅲ) content increases rapidly, the melt becomes saturated, Fe3O4 first precipitates and crystal particles grow up.

4) Appropriate thermal conditions do good to the growth of magnetite(Fe3O4) crystal particles. The average particle size is 90-100μm when cooled down at 5K/min, while the particles is of good autotype.

REFERENCES

[1]Yazawa A. Thermodynamic considerations of copper smelting [J]. Canadian Metallurgy Quartt, 1974, 13(3): 443-454.

[2]Sridhar R, Toguri J M. Thermodynamic considerations in the pyrometallurgical production of copper [J]. Challenges in Process Intensification, Montreal, Quebec, 1996, 8: 24-29.

[3]Kaiura G H, Toguri J M, Marchant G. Viscosity of fayalite-base slags [A]. Metallurgical Society of CIM Annuel Volume Featuring Molybdenum [C]. Montreal, Quebec Canadian, 1979. 156-160.

[4]Vartiainen A. Viscosity of iron-silicate slag at copper smelting conditions [A]. Sulfide Smelting 98 [C]. San Antonio, Texas, 1998. 363-372.

[5]DAI Xi, GAN Xue-ping, ZHANG Chuan-fu. Viscosities of FenO-MgO-SiO2 and FenO-MgO-CaO-SiO2 slags [J]. Trans Nonferrous Met Soc China, 2003, 13(6): 1451-1453.

[6]Moskalyk R R, Alfantazi A M. Review of copper pyrometallurgical practice: today and tomorrow [J]. Minerals Engineering, 2003, 16: 893-919.

[7]Kongoli F, McBow I, Llubani S. Effect of the oxygen potential on the viscosity of copper smelting slag [A]. Yazawa International Symposium on Metallurgical and Materials Processing: Principles and Technologies: High-Temperature Metal Production [C]. San Diego, California, USA, 2003. 305-316.

[8]Goel R P, Kellogg H H, larrain J. Mathematical description of the thermodynamic properties of the systems Fe-O and Fe-O-SiO2 [J]. Metallurgical Transactions B, 1980, 11B: 107-117.

[9]Sohn H Y. The influence of chemical equilibrium on fluid-solid reaction rates and the falsification of activation energy [J]. Metallurgical and Materials Trans, 2004, 35B(2): 121-131.

[10]Lifset R J, Gordon R B. Where has all the copper gone: the stocks and flows project, part 1 [J]. JOM, 2002, 10: 21-26.

[11]Kim H G, Sohn H Y. Minor-element behavior and iron partition during the cleaning of copper converter slag under reducing conditions [J]. Canadian Metallurgy Quarterly, 1997, 36(1): 31-37.

[12]Matousek J W. The oxidation mechanism in copper smelting and converting [J]. JOM, 1998, 50(4): 64-65.

[13]Li Y, Racthey I P, Lucas J A. Rate of interfacial reaction between liquid iron oxide and CO-CO2 [J]. Metallurgy and Material Transactions, 2000, 31B(5): 1049-1057.

[14]ZHOU Tong-hui. Analytical Chemistry Handbook(Ⅱ)[M]. Beijing: Chemical Industry Press,1997.

[15]Jung I A, Decterov S A, Pelton A D. Critical thermodynamic evaluation and optimization of FeO-Fe2O3-MgO-SiO2 system [J]. Metallurgical and Materials Trans, 2004, 35B(10): 877-889.

[16]ZHAO Yu-xiang, SHEN Yi-shen. Modern Metallurgy Principle [M]. Beijing: Metallurgy Industry Press, 1993. 156.

[17]LIAN Lian-ke, CHE Yin-chang. Thermodynamic and Kinetic of Metallurgy [M]. Shenyang: Northeastern University Press, 1990. 231.

[18]Sun Y, Jahanshahi S. Redox equilibria and kinetics of gas-slag reactions [J]. Metallurgical and Materials Trans B, 2000, 31B(10): 939-946.

Foundation item: Key Project(50234040) supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China

Received date: 2004-11-08; Accepted date:2005-01-25

Correspondence: ZHANG Lin-nan, PhD; Tel: +86-24-83681310; E-mail: zln2277@263.net