Trans. Nonferrous Met. Soc. China 26(2016) 684-696

Corrosion evaluation of friction stir welded lap joints of AA6061-T6 aluminum alloy

Farhad GHARAVI1, Khamirul A. MATORI1,2, Robiah YUNUS1, Norinsan K. OTHMAN3, Firouz FADAEIFARD1

1. Materials Synthesis and Characterization Laboratory, Institute of Advanced Technology, Universiti Putra Malaysia, 43400 UPM Serdang, Selangor, Malaysia;

2. Department of Physics, Faculty of Science, Universiti Putra Malaysia, 43400 UPM Serdang, Selangor, Malaysia;

3. Schools of Applied Physics, Faculty of Science and Technology, University Kebangsaan Malaysia, 43600 UKM Bangi, Selangor, Malaysia

Received 24 February 2015; accepted 11 January 2016

Abstract:

Corrosion behavior of friction stir lap welded AA6061-T6 aluminum alloy was investigated by immersion tests in sodium chloride + hydrogen peroxide solution. Electrochemical measurement by cyclic potentiodynamic polarization, scanning electron microscopy, and energy dispersive spectroscopy were employed to characterize corrosion morphology and to realize corrosion mechanism of weld regions as opposed to the parent alloy. The microstructure and shear strength of welded joint were fully investigated. The results indicate that, compared with the parent alloy, the weld regions are susceptible to intergranular and pitting attacks in the test solution during immersion time. The obtained results of lap shear testing disclose that tensile shear strength of the welds is 128 MPa which is more than 60% of the strength of parent alloy in lap shear testing. Electrochemical results show that the protection potentials of the WNZ and HAZ regions are more negative than the pitting potential. This means that the WNZ and HAZ regions do not show more tendencies to pitting corrosion. Corrosion resistance of parent alloy is higher than that for the weldments, and the lowest corrosion resistance is related to the heat affected zone. The pitting attacks originate from the edge of intermetallic particles as the cathode compared with the Al matrix due to their high self-corrosion potential. It is supposed that by increasing intermetallic particle distributed throughout the matrix of weld regions, the galvanic corrosion couples are increased, and hence decrease the corrosion resistance of weld regions.

Key words:

friction stir welding; lap joints; AA6061 alloy; pitting corrosion; welding process; intermetallic particles;

1 Introduction

As an emerging green solid state joining process, friction stir welding (FSW) is used to join Al alloys of all compositions such as alloys essentially considered unweldable [1]. In this process, joining metal plates are done based on a thermo-mechanical action used by a non-consumable welding tool onto metal plates [1]. Most AA6xxx alloys are generally considered to have good corrosion resistance compared with other series of aluminum alloys. However, some treatments or processes such as thermomechanical treatment or alloying have an effect on the localized corrosion alloys. Accordingly, the treatments or processes can lead to create a pitting corrosion and intergranular corrosion (IGC) in the alloys [2]. In fact, FSW is a thermomechanical treatment, which combines frictional heating and stirring motion to soften and mix the interface between two metal plates to produce fully consolidated welds [3]. Although the heat input in the FSW process is relatively low and the time at process temperature is short compared with fusion welding, various grain structures and grains recrystallization phenomena dynamically occurring during the FSW process, in 6xxx series of stir welded Al alloy, have different corrosion susceptibilities in each area of the jointed zone. In FSW process, generally, in the weld nugget zone (WNZ), and heat affected zone (HAZ), the time at peak temperature is short, and cooling is relatively rapid. In this case, a corresponding microstructural gradient can be developed from the WNZ into the parent alloy (PA) with the precipitation distribution at and around grain boundaries as a result of temperature excursions [3]. When exposed to a corrosive environment, some of these microstructures exhibit a selective grain boundary attack, and the pitting potential is decreased as opposed to the parent alloy. As a matter of fact, the response of the microstructure to the welding is intense, and intergranular corrosion (IGC) is mainly placed along the interface of the WNZ and HAZ. In this respect, the IGC attack increases as a result of coarsening of the grain boundary precipitates [4]. The IGC initiation is generally believed to begin along the precipitate regions. Accordingly, the created pits and intergranular attack connect together and grow as microstructural pits, which result in selective corrosion of grains [4]. There is a limited research on the relationship between microstructure and corrosion characteristics of friction stir lap welded Al alloy. The purpose of the present work is to evaluate how the changes in microstructure in the weld zone affect corrosion behavior.

2 Experimental

2.1 Materials and welding parameters

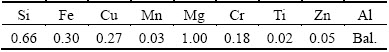

By applying automatic CNC machine, friction stir welding technique was used to produce lap welds. The materials used were AA6061-T6 aluminum plates with the thickness of 5 mm. The nominal composition is displayed in Table 1. The lap joint configuration was prepared to produce the joints. The direction of welding was normal to the rolling direction of aluminum plates. A non-consumable welding tool made of high carbon steel (H13) was applied to fabricating the joints. The welding conditions used to produce the joints in this investigation are listed in Table 2. The schematic representation of welding process and joint design are shown in Fig. 1.

Table 1 Chemical composition of Al6061 parent alloy used in welding process (mass fraction, %)

Table 2 Welding conditions and process parameters used in this work

Fig. 1 Schematic of friction stir lap welding process and joint design used in this research

2.2 Lap shear test

In order to investigate the mechanical property of welded joint, room temperature lap shear tests were performed by using a 100 kN Instron mechanical testing machine with the cross head speed fixed at 2.0 mm/min. Due to no test standards for friction stir welded lap joints, ASTM: D3164 [5] providing test method for strength properties of adhesively bonded joints was chosen as the reference test standard for lap shear test. Dimensions of the samples used for lap shear testing is longer than those used by CEDERQVIST and REYNOLDS [6]. For tensile shear-testing specimen, fracture locations were recorded by scanning electron microscopy (SEM).

2.3 Immersion corrosion test

In the present research, the behavior against the IGC of friction stir welded lap joints of AA6061 aluminum alloy has been studied under specific conditions. Immersion corrosion tests were performed by using the ASTM G110 [7]. The tests were carried out for 24 and 48 h immersion time with a constant concentration of hydrogen peroxide based on ASTM standard [7]. After immersion tests, the corroded specimens were subjected to the surface cleaning procedure recommended in ASTM standard [8].

2.4 Electrochemical measurements

Electrochemical measurements were carried out with a conventional three-electrode-electrochemical glass cell using an EG&G Princeton Applied Research 2273 Potentiostat controlled by softcorr 352. The cell was opened to the air and the measurements were conducted at ambient temperature. Each set of working electrodes, which were the WNZ (weld nugget zone), HAZ (heat affected zone), and parent alloy (PA) specimens, was connected to a copper wire, and sealed in epoxy resin with the exposure area of 1 cm2 for the PA and 0.8 cm2 for the WNZ as well as 0.3 cm2 for the HAZ. The graphite rod was used as the auxiliary electrode, and the saturated chalomel electrode (SCE) as a reference electrode. During the measurement, the solution was not stirred. All potential values were reported in mV (SCE). The exposed surface of each specimen was ground using abrasive SiC papers through 600-grade to 1200-grade, and were mechanically polished with 1 μm diamond paste, rinsed with double distilled water, and degreased with ethanol. The degreased working electrodes were then dipped in concentrated HNO3 for 30 s. After that, they were rinsed with deionized water and inserted into 3.5% (mass fraction) NaCl solution.

After 30 min of immersion in the electrolyte, the cyclic potentiodynamic polarization (CPP) of specimens were performed by starting scanning electrode potential from an initial potential of -0.25 V below the OCP up to -0.2 V. The scan direction then was reversed and the potentials were scanned back to the initial potential. A vertex current density of 0.001 A/cm2 was applied. From cyclic polarization, various corrosion parameters such as corrosion potential (φcorr), pitting potential (φpit), repassivation/protection potential (φprot), and pit transition potential (φptp) were obtained.

2.5 Microstructure characterization

Microstructural examination of AA6061-T6 welded lap joints before and after corrosion tests were analyzed by scanning electron microscopy (SEM) with energy dispersive spectroscopy (EDS) and atomic force microscopy (AFM) techniques.

3 Results and discussion

3.1 Mechanical properties

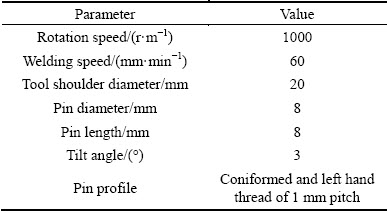

The obtained tensile shear strength of the welds was (128±5) MPa (whereas the shear stress of AA6061-T6 is 207 MPa [9]) as a mean of four tests of this welded joint. This demonstrates more than 60% of the strength of parent alloy in lap shear testing. The fracture path was through the weld along the interface of top and bottom sheet whereas it was propagated from advancing side toward retreating side. The SEM image of fracture surface predominately shows a brittle fracture as indicated in Fig. 2.

Fig. 2 SEM image of fracture surface

3.2 Microstructural analysis

3.2.1 Microstructure of parent alloy (PA)

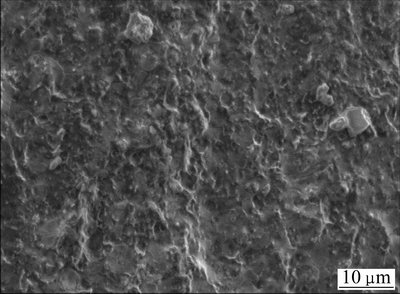

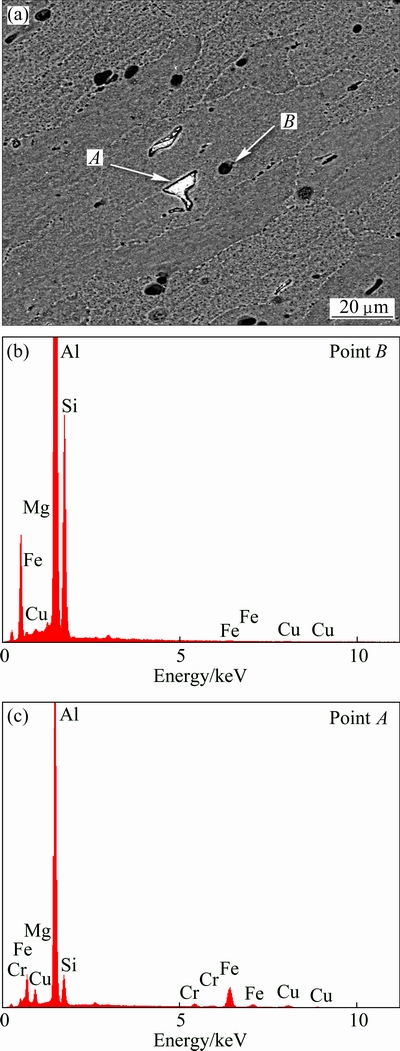

The parent alloy exhibited elongated alpha grains, the sizes of which are less homogeneous in size and the lengths of them are around 50 μm. Moreover, the PA also displayed two kinds of intermetallic particles including inhomogeneous distributed semi-round particles and irregular-shaped particles, as shown in Fig. 3(a) [10]. According to Figs. 3(a) and 3(b), EDS point analysis performed on these particles disclosed that irregular-shaped particles which appeared in bright color (point A) contained the Fe-rich particles, whereas semi-round particles which appeared in dark color (point B) contained the Si-rich particles. It was also observed that the size of Fe-rich particles present in the Al matrix is comparable to that of the Si-rich particles. This can be attributed to the chemical composition of plate and its heat treatment condition. Additionally, as shown in Fig. 4, a lot of small grain boundary phases (dark points) can also be seen at the grain boundaries. As illustrated in Fig. 4(b), EDS point analysis displayed that these particles are rich in Si phases. As a matter of fact, these precipitates cause an increase in the strength of parent alloy. This means that they act as strengthening precipitates in the parent alloy. Thus, the strengthening precipitates can affect localized corrosion of parent alloy in corrosive environments.

Fig. 3 BSE micrograph of PA (a) and associated EDX analysis taken at indicated locations (b, c)

Fig. 4 BSE micrographs of small grain boundary phases in parent alloy (PA) (a, b) and associated EDX analysis (c)

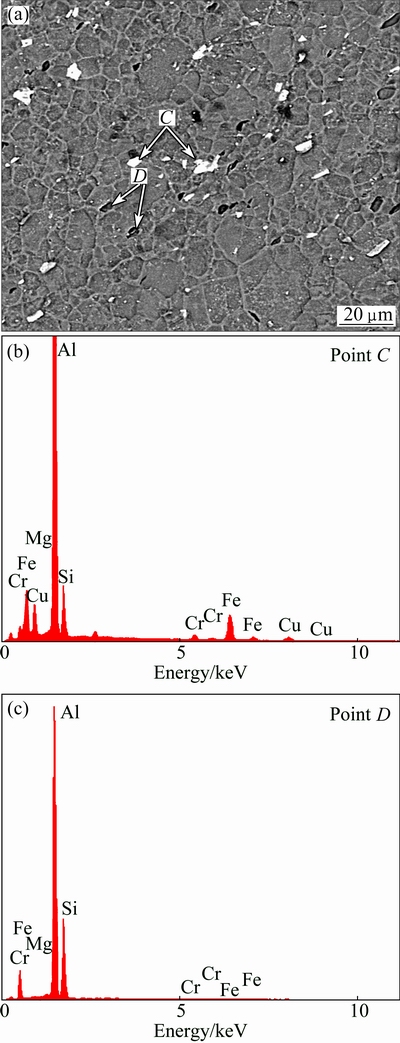

Fig. 5 BSE micrograph of HAZ (a) and associated EDX analysis taken at indicated locations (b, c)

3.2.2 Microstructure of weld regions

Backscattered electron micrographs of grains and distribution of intermetallic particles in the WNZ and the HAZ regions of welded lap joint are shown in Figs. 5 and 6, respectively. As can be seen in Fig. 5, the prominent feature is obvious difference of the size and shape of the grains in the HAZ region. The HAZ area exhibited bigger grains than the WNZ region (Fig. 6), due to the heating effect. In this regards, according to ASTM E562 standard [11], the average volume fractions of intermetallics in the WNZ and HAZ are about 0.02 and 0.04, respectively. The HAZ experiences heating without mechanical deformation during welding. Thus, the induced heat in this region and the cooling rate after FSLW can significantly alter the grain size and lead to grains coarsening in the HAZ region. On the contrary, the structure of WNZ region contains fine and equiaxed grains. This structure is a typical feature of dynamically recrystallized structure when the WNZ is subjected to high temperature and extensive plastic deformation [12].

Fig. 6 BSE micrograph of WNZ (a) and associated EDX analysis taken at indicated locations (b, c)

The results of EDX analysis of two different intermetallic precipitates are shown in Figs. 5(b,c) and 6(b,c). From the EDS point analysis, it is easy to identify two particles: the Fe-rich particles (bright points, labeled as C and E) and the Si-rich particles (dark points, denoted as D and F). According to Figs. 5(a) and 6(a), the sizes of iron- and silicon-rich particles in the HAZ region are bigger than that in the WNZ area. This can be attributed to that in the WNZ region, the string crashed the intermetallic particles and distributed them into the Al matrix. The number of intermetallic particles in the WNZ region is higher than that in the HAZ region, but their volume fraction is lower. As matter of fact, it can be said that the intermetallic particles are the main factor that controls the corrosion properties of the parent alloy and weldments and the corrosion resistance of weldments is basically affected by the composition, density and distribution of intermetallic particles within the microstructure [10,13].

3.3 Corrosion morphology analysis

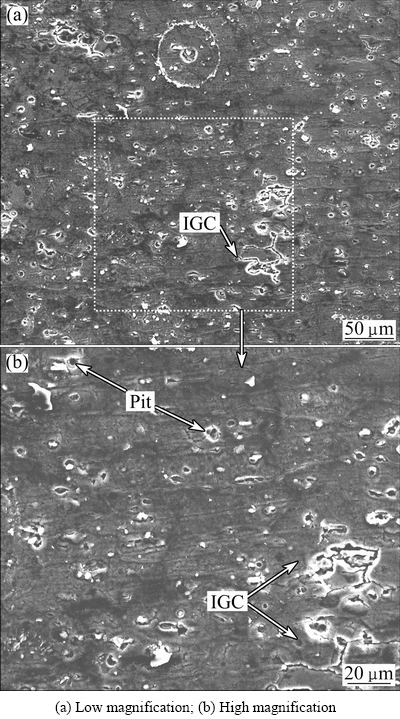

3.3.1 Microstructure of parent alloy after 24 h of immersion

Figure 7 presents the corrosion morphology of the parent alloy after 24 h of immersion in the test solution. According to Fig. 7, it is obvious that localized corrosion, i.e., tunnel like pitting, is not the dominant corrosion type observed in the parent alloy, and it also shows susceptibility to intergranular corrosion along grain boundaries. Accordingly, it is important to consider that the pits formed in the matrix have no growths in depth and size due to the lack of immersion time, and it seems that many small pits in an early stage are formed on Al matrix with ring-like deposits (corrosion products) consisting of oxy-hydroxide compounds around the pits [12]. It can be said that the corrosion products are formed where Al ions become oversaturated due to local dissolution of the Al matrix. Indeed, the IGC mechanism including micro galvanic cell formation of grain boundaries can contribute to the grain boundaries intermetallic precipitates so that they are either more active or nobler than the surrounding Al matrix (Fig. 4 and Fig. 7). Overall, it seems that the formation of small pits with lower growth in depth and size as well as lower intergranular corrosion along grain boundaries implies minor susceptibility to localized corrosion in parent alloy after 24 h of immersion.

Fig. 7 SEM images of parent alloy after 24 h of immersion

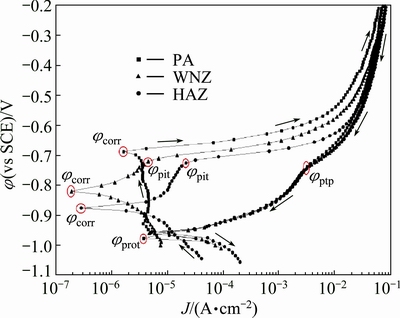

3.3.2 Microstructure of parent alloy after 48 h of immersion

According to Fig. 7, it is obvious that localized corrosion attacks were generated by semi-pitting and intergranular attacks. In this case, it seems that the grooves, that so-called circumferential pit, were formed around strengthening precipitates due to the cathodic reduction of oxygen, and occurred at the intermetallic particles. They caused an increment in the pH of the solution to alkalinity around the particles, leading to the dissolution of Al matrix, ascribed to the localized galvanic attack of the more active matrix by the more noble particles [13]. A relevant fact observable from the images in Fig. 8 was that when the immersion time was extended to 48 h, intergranular corrosion attacks were the main feature in Al matrix, and they grow widely on it. Finally, it seems that the formation of semi-pits with high growth in depth and size as well as higher intergranular corrosion along grain boundaries implies major susceptibility to localized corrosion in parent alloy after 48 h immersion.

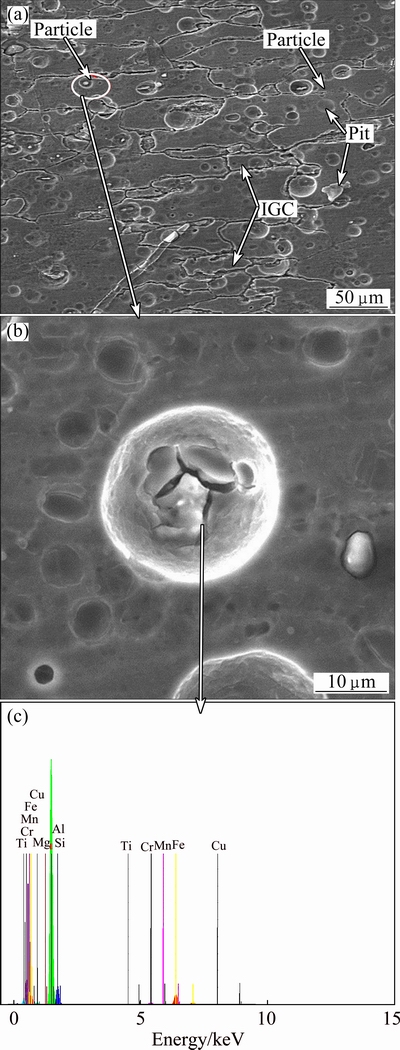

3.3.3 Microstructure of welded lap joint after 24 h of immersion

Microscopic images of corrosion attack of the lap welded specimens after 24 h of immersion in 5.7% sodium chloride and 0.3% hydrogen peroxide solutions are shown in Fig. 9, revealing the following important findings.

First, although all areas show the same corrosion attacks, the HAZ shows higher rate of corrosion attack than the WNZ due to a bigger size and more intermetallic particles in the interior grain and grain boundaries (Figs. 5 and 6). Additionally, the IGC was not the dominant corrosion type in the weld regions. Second, the evidence of cathodic reactivity of the kinds of rings of attack around constituent intermetallic particles can be explained as corrosion attack mechanism in the weld zones. In this regard, the rings of attack (or grooves) around the intact intermetallic particles were ascribed to the localized galvanic attack of the more active Al matrix by the more noble particle. Third, the corrosion products that were naturally formed as the aluminium hydroxyl chloride compounds (AlClx[OH]3-x) [4] were not observed in the WNZ and HAZ.

Fig. 8 SEM images of parent alloy after 48 h of immersion (a, b) and associated EDX analysis (c)

3.3.4 Microstructure of welded lap joint after 48 h of immersion

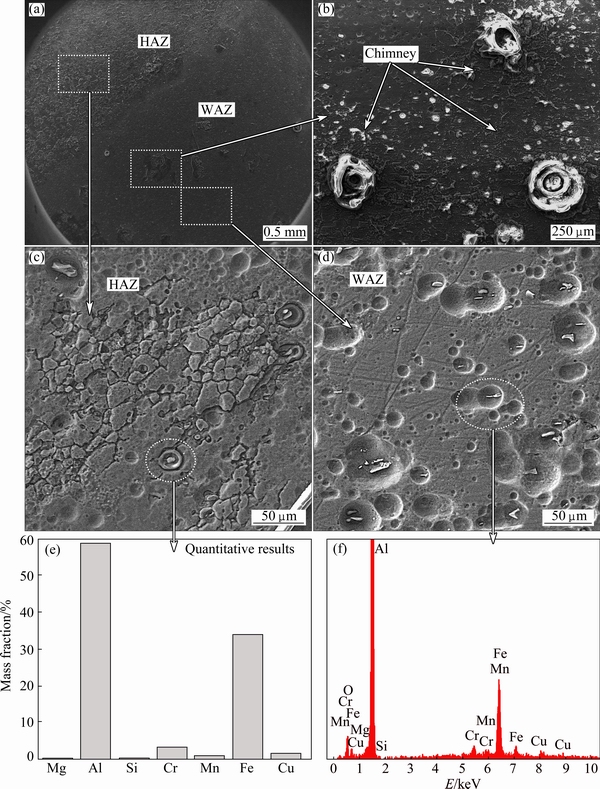

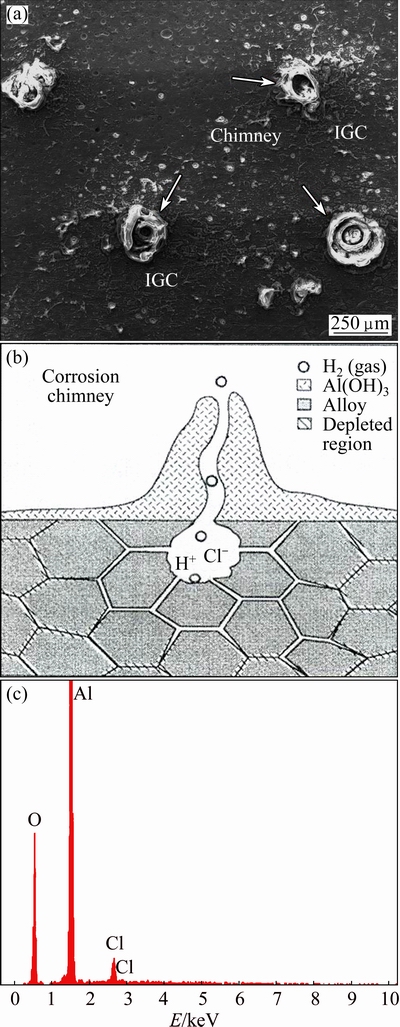

Figure 10 depicts the microscopic images of corrosion attack of the lap welded specimens after 48 h of immersion in the test solution. Some important findings are explained as follows.

First, the intensive corrosion attack in the nugget region is poorer than that in the other regions. In this case, although corrosion resistance of the WNZ is higher than that of the HAZ region, by increasing the immersion time (48 h), some corrosion chimneys are observed in this region (see Fig. 11). Second, in the nugget region, despite other regions, the corrosion products form only as a corrosion chimney product. This means that the corrosion products are only formed locally on the surface of the WNZ. Third, both formations of grooves around the intermetallic precipitates and the corrosion chimney were dominant corrosion types in the nugget region. Fourth, the value of corrosion attacks in the HAZ region was more intensive than that in the WNZ. In this case, it seems that the corrosion chimneys are uniformly created in the HAZ region, and the corrosion products cover the whole surface of the HAZ area. In addition, it is observed that the depth of grooves formed in these areas is more than that in the WNZ. As a result, it seems that by increasing immersion time, the corrosion behavior of weld regions is different, and the corrosion attacks will be increased intensively.

Fig. 9 SEM images of corrosion attacks in weld regions after 24 h of immersion (a, b, c, d) and associated EDX analysis (e)

Fig. 10 SEM images of corrosion attacks in weld regions after 48 h of immersion (a, b, c, d) and associated EDX analysis (e, f)

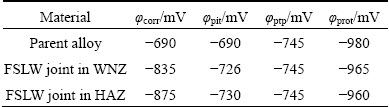

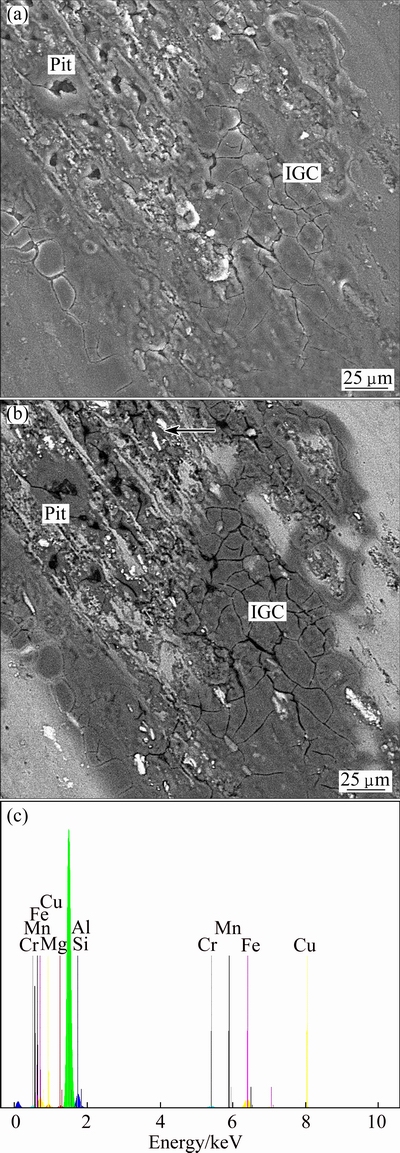

3.4 Electrochemical measurement

Cyclic potentiodynamic polarization (CPP) plots obtained for the parent alloy and weld regions in contact with 3.5% NaCl solution having near natural pH are shown in Fig. 12. The average values of potentials are summarized in Table 3.

From Table 3, it is evident that the almost similar values of φpit for the WNZ and HAZ regions of welded lap joints in test solution may indicate that the onset of pitting is mainly determined by Cl- ion concentration and not by O2 content [14]. According to Fig. 12, it is obvious that the cyclic plots of parent alloy and each region of welded lap joint show an example of negative hysteresis, with pitting potential located at the same position of that of corrosion potential, the protection potential (φprot) less than φcorr, and narrow area of the hysteresis loop, suggesting no nucleation and growth of pitting during the reverse scan [14,15]. The lower hysteresis in the presence of oxygen is due to repassivation assisted by O2 reduction on constituent particles sites, indicating that not all such species have been consumed in accelerating pitting corrosion. Moreover, the protection potentials of the WNZ and HAZ regions are more negative than the pitting potential. This means that the WNZ and HAZ regions did not show more tendencies to pitting corrosion. The solid arrows next to the forward and the reverse anodic branches indicate potential scan direction. The cyclic polarization curves show a small region of passivity with the current density practically dependent on applied potential up to pitting potential φpit=-0.750 mV. Then, the current density increases abruptly until it reaches a certain value; after that, it continues to increase slightly with increasing potential.

Fig. 11 Corrosion chimney in WNZ (a), cross section of corrosion chimney [4] (b), and associated EDX analysis of corrosion products (c)

Table 3 Average characteristic potentials of parent alloy and welded lap joint from pitting scans

Furthermore, it is clear that the protection potential (φprot) is less than φcorr in lap welded joints. It is well established that the size of the pitting loop is a rough indication of pitting tendency [14-16], so, the loop created in cyclic polarization plots shows the smallest tendency to pitting corrosion. Narrower hysteresis and, consequently, more negative φprot than φcorr, are obtained for welded lap joints. Indeed, a potential step in the reverse scan, the so-called pit transition potential (φptp), is detected for lap welded joints. Additionally, φptp occurrence with different abruptnesses at the step (change of slope) is obtained for welded lap joints [10,12,13]. This indicates that the hysteresis features of cyclic polarization depend on the nature of the parent alloy and welding parameters under the present experimental conditions. In this respect, it is clear that the change of slope is sharper in all joints. This behavior shows that the tendency of all joints to repassivation is high. The remarkable features of the reverse scan among the welded joints allow the qualitative discrimination of the localized corrosion behavior. Analyses of the hysteresis loop and the corresponding shift in φprot indicate that the amount of pit propagation with consequent difficulty to complete surface repassivation is increased to near the corrosion potential. Thus, the welded joint shows higher susceptibility to pitting corrosion. According to these results, the significance of φprot is almost misleading, not allowing discrimination between pitting corrosion and other possible forms of localized corrosion with more restricted conditions such as intergranular corrosion (IGC).

Fig. 12 CPP curves of parent alloy and weld regions

Fig. 13 SEM images of parent alloy (PA) surface (a, b) and associated EDX analysis taken at indicated location after pitting scans (c)

Fig. 14 SEM images of WNZ surfaces (a, b) and associated EDX analysis taken at indicated location after pitting scans (c)

Figures 13-15 report a magnification of the surfaces of the parent alloy, the WNZ and HAZ after the cyclic polarization test. A careful observation of these pictures reveals that lap welded joints showing marked intergranular attacks (pointed as IG) exhibit a φptp transition in the cyclic polarization plot of Fig. 12. Several authors reported that pitting and intergranular corrosions were often encountered together in aluminum alloys [17-19]. The intergranular corrosion nucleates on pit walls and spreads from them. When the pitting is established in a relatively continuous network along grain boundaries, the intergranular corrosion develops. The variation in pit shape mainly depends on the microstructure of parent alloy composition and welding conditions. It has to be noted that the SEM images of the corroded surfaces of the parent alloy and welded lap joints after cyclic polarization experiments strongly support the electrochemical measurements feature. In this case, these micrographs clearly show that the damages caused by these types of corrosion are accentuated in near-natural solution, suggesting that the corrosion resistance of the welded joints in each region was lower than the parent alloy. It is to be noted that pitting attacks were observed on the WNZ and HAZ (Figs. 14 and 15). It can be seen that the density and size of pits in the WNZ are lower in comparison to those in the HAZ region. Hence, the HAZ region showed poor resistance to corrosion.

Fig. 15 SEM images of HAZ surfaces (a, b) and associated EDX analysis taken at indicated location after pitting scans (c)

According to Fig. 13, it is observed that a film, which is generated by corrosion products (dark area in Fig. 13(b)), shows cracks that are not compact and are almost heterogeneous. These cracks could be related to the intergranular corrosion in the parent alloy after the corrosion test. As for the friction stir lap welds, the weld regions, especially the HAZ, suffer more severe pitting compared with the parent alloy. It is to be noted that the galvanic corrosion exists between the weld regions and the constituent particles, which have differences in chemical composition and microstructure. In this case, it is supposed that the cathodic process at the constituent particles causes a local increase in pH that in turn leads to the dissolution of Al matrix and also may be the surface film resulting in the porous surface layer. Corrosion potential of an intermetallic particle is not the same as the Al matrix phase. This variation in potential creates the formation of a galvanic cell [20]. The potential difference between intermetallic particles and Al matrix causes the formation of corrosion cells. It can be noticed that higher amounts of intermetallic particles lead to more cathodic reactions. In this respect, increase in constituent particles increases the sites for galvanic coupling, and hence, decreases the corrosion resistance [21]. Localized galvanic corrosion between constituent particles and the Al matrix increases. The enhanced hydrogen evolution also exists in the cathodic constituent particles in the weld regions [20]. This study suggests that increase in pitting and intergranular attack in the weld regions can be attributed to the increased constituent particles for the friction stir lap welds.

Figure 16 displays three-dimensional images of the parent alloy sample surface as well as those for the WNZ and the HAZ after the corrosion test. This figure presents a good amount of quantitative data related to the corrosion attacks occurring on the sample surfaces. Compared with the parent alloy, the amount of corrosion attacks increased significantly from the WNZ to the HAZ for FSLW, and the intensity of corrosion attacks on the surfaces of the FSLW samples is greater than that of the parent alloy samples. As seen in Fig. 16, the surface roughness of the WNZ and the HAZ for FSLW is greater than that for parent alloy. The increase in surface roughness for the FSLW samples can be attributed to the severe chemical dissolution of the intermetallic particles and the Al matrix. As a result, the susceptibility to corrosion attacks in the HAZ for FSLW is higher than that in the WNZ as opposed to the parent alloy.

4 Conclusions

The strength of welded joint obtained at least 60% of the shear strength of parent alloy. However, the size of particles after FSLW process was decreased as opposed to the parent alloy and particles size in the WNZ was smaller than that in the HAZ. The HAZ in all welded samples were the most susceptible to intergranular corrosion after 48 h of immersion as opposed to that after 24 h of immersion in both welding conditions. After 24 h of immersion, parent alloy was susceptible to pitting corrosion and intergranular attack, but after 48 h immersion, it showed transgranular attack and pitting corrosion. SEM images showed the corrosion chimney over the corrosion pits in the weld nugget zone after 48 h immersion. The corrosion pits revealed linked to IGC since the pit electrolyte could preferentially corrode the grain boundaries. The increased intermetallic constituent particles during welding process increased the galvanic corrosion coupling, and hence decreased the corrosion resistance of weld regions. Finally, these results proved by the corrosion attack morphology in the SEM and AFM images, suggest that the corrosion resistance in different weld regions for the FSLW samples is poorer than that for the parent alloy.

Fig. 16 Three-dimensional AFM images of weld regions surface after pitting scans

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to express sincere special thanks to Dr. Mohd Khairol Anuar Mohd Ariffin, Head of Department of Mechanical and Manufacturing, Faculty of Engineering, Universiti Putra Malaysia (UPM) for their technical supports. Also, the authors are grateful to Prof. Abdul Razak Daud from the School of Applied Physics, Faculty of Science and Technology, University Kebangsaan Malaysia (UKM) for his help and guidance to do this research.

References

[1] THOMAS W M, NICHOLAS E D, NEEDHAM J C, CHURCH M G, TEMPLESMITH P, DAWES C. Intl patent application No. PCT/GB92/02203 and GB Patent Application No. 9125978.9, 1991. [P]. 1991.

[2] ZHAN H, MOL J M C, HANNOUR F, ZHUANG L, TERRYN H, WIT J H W. The influence of copper content on intergranular corrosion of model AlMgSi(Cu) alloys [J]. Materials and Corrosion, 2008, 59: 670-675.

[3] PAGLIA C S, BUCHHEIT R G. A look in the corrosion of aluminum alloy friction stir welds [J]. Scripta Materialia, 2008, 58: 383-387.

[4] LUMSDEN J B, MAHONEY M W, POLLOCK G, RHODES C G. Intergranular corrosion following friction stir welding of aluminium alloy 7075-T651 [J]. Corrosion, 1999, 55: 1127-1135.

[5] ASTM: D-3164. Standard test method for strength properties of adhesively bonded plastic lap shear sandwich joints in shear by tension loading [S].

[6] CEDERQVIST L, REYNOLDS A P. Factors affecting the properties of friction stir welded aluminium lap joints [J]. Welding Journal, 2001, 80 (12): 281-287.

[7] ASTM: G-110-92. Practice for evaluating intergranular corrosion resistance of heat-treatable aluminum alloys by immersion in sodium chloride+ hydrogen peroxide solution [S].

[8] ASTM: G-1-03. Standard practice for preparing, cleaning, and evaluating corrosion test specimens [S].

[9] ASTM: B0209M-04. Aluminium and magnesium alloys, specification for aluminium and aluminium-alloy sheet and plate [S].

[10] GHARAVI F, MATORI K A, YUNUS R, OTHMAN N K, FADAEIFARD F. Corrosion behaviour of friction stir welded lap joints of AA6061-T6 aluminium alloy [J]. Materials Research, 2014, 17(3): 672-681.

[11] ASTM: E-562-11. Standard test method for determining volume fraction by systematic manual point count [S].

[12] JARIYABOON M, DAVENPORT A J, AMBAT R, CONNOLLY B J, WILLIAMS S W, PRICE D A. The effect of welding parameters on the corrosion behavior of friction stir welded AA2024-T351 [J]. Corrosion Science, 2007, 49: 877-909.

[13] BIRBILIS N, BUCHHEIT R G. Electrochemical characteristics of intermetallic phases in aluminium alloys an experimental survey and discussion [J]. Journal of Electrochemical Society, 2005, 152: 140-151.

[14] TRUEBA M, TRASATTI S P. Study of al alloy corrosion in neutral NaCl by the pitting scan technique [J]. Materials Chemistry and Physic, 2010, 121: 523-533.

[15] ZAID B, SAIDI D, BENZAID A, HADJI S. Effects of pH and chloride concentration on pitting corrosion of AA6061 aluminum alloy [J]. Corrosion Science, 2008, 50: 1841-1847.

[16] BIRBILLIS N, BUCHHEIT R G. Investigation and discussion of characteristics for intermetallic phases common to aluminum alloys as a function of solution pH [J]. Journal of Electrochemical Society, 2008, 155: 117-126.

[17] ASTARITA A, BITONDO C, SQUILLACE A, ARENTANI E, BELLUCCI F. Stress corrosion cracking behaviour of conventional and innovative aluminium alloys for aeronautic applications [J]. Surface Interface Analysis, 2013, 45: 1610-1618.

[18] VARGEL C, JACQUES M, SCHMIDT M P. Corrosion of aluminum [M]. Amsterdam: Elsevier, 2004.

[19] AMINI M, KAZEMZADE F, MOAYED M H. An approach to predict galvanic corrosion using identical couple electrodes; investigation of weld zone and parent alloy in AA6xxx welded through FSW technique [C]//Proceedings of Iran International Aluminum Conference (IIAC2009): Tehran, 2009.

[20] ZHANG D, LI J, JOO H G, LEE K Y. Corrosion properties of ND: YAG laser–GMA hybrid welded AA6061 Al alloy and its microstructure [J]. Corrosion Science, 2009, 51: 1399-1404.

[21] EL-MENSHAWY K, EL-SAYED A, EL-BEDAWY M E, AHMED H A, EL-RAGHY S M. Effect of aging time at low aging temperatures on the corrosion of aluminium alloy 6061 [J]. Corrosion Science, 2012, 54: 167-173.

AA6061-T6合金搅拌摩擦焊搭接接头的腐蚀性能评价

Farhad GHARAVI1, Khamirul A. MATORI1,2, Robiah YUNUS1, Norinsan K. OTHMAN3, Firouz FADAEIFARD1

1. Materials Synthesis and Characterization Laboratory, Institute of Advanced Technology, Universiti Putra Malaysia, 43400 UPM Serdang, Selangor, Malaysia;

2. Department of Physics, Faculty of Science, Universiti Putra Malaysia, 43400 UPM Serdang, Selangor, Malaysia;

3. Schools of Applied Physics, Faculty of Science and Technology, University Kebangsaan Malaysia, 43600 UKM Bangi, Selangor, Malaysia

摘 要:采用氯化钠+过氧化氢溶液浸泡试验研究AA6061-T6铝合金搅拌摩擦焊搭接接头的腐蚀行为。采用循环动电位极化测试、扫描电子显微镜和能谱仪表征腐蚀形貌,揭示焊接区与基体合金的腐蚀机理。研究了焊接接头的显微组织和剪切强度。结果表明,与基体合金相比,焊接区在腐蚀溶液中会发生晶间腐蚀和点蚀。搭接剪切测试结果表明,所得焊接接头的拉伸剪切强度为128 MPa, 超过基体合金强度的60%。电化学测试结果表明,焊核区和热影响区的保护电位比点蚀电位更负,说明焊核区与热影响区点蚀的趋势不强。基体合金抗腐蚀性比焊缝区的强,而热影响区的抗腐蚀性最差。点蚀主要源于金属间化合物边缘,因为与铝基体相比,金属间化合物的自腐蚀电位更高而成为阴极。由于焊缝区的金属间化合物增加,腐蚀电偶增加,焊缝的抗腐蚀性降低。

关键词:搅拌摩擦焊;搭接接头;AA6061合金;点蚀;焊接过程;金属间化合物

(Edited by Yun-bin HE)

Corresponding author: Khamirul A. MATORI; Tel: +6-03-89466653; E-mail: khamirul@upm.edu.my

DOI: 10.1016/S1003-6326(16)64159-6

Abstract: Corrosion behavior of friction stir lap welded AA6061-T6 aluminum alloy was investigated by immersion tests in sodium chloride + hydrogen peroxide solution. Electrochemical measurement by cyclic potentiodynamic polarization, scanning electron microscopy, and energy dispersive spectroscopy were employed to characterize corrosion morphology and to realize corrosion mechanism of weld regions as opposed to the parent alloy. The microstructure and shear strength of welded joint were fully investigated. The results indicate that, compared with the parent alloy, the weld regions are susceptible to intergranular and pitting attacks in the test solution during immersion time. The obtained results of lap shear testing disclose that tensile shear strength of the welds is 128 MPa which is more than 60% of the strength of parent alloy in lap shear testing. Electrochemical results show that the protection potentials of the WNZ and HAZ regions are more negative than the pitting potential. This means that the WNZ and HAZ regions do not show more tendencies to pitting corrosion. Corrosion resistance of parent alloy is higher than that for the weldments, and the lowest corrosion resistance is related to the heat affected zone. The pitting attacks originate from the edge of intermetallic particles as the cathode compared with the Al matrix due to their high self-corrosion potential. It is supposed that by increasing intermetallic particle distributed throughout the matrix of weld regions, the galvanic corrosion couples are increased, and hence decrease the corrosion resistance of weld regions.