Trans. Nonferrous Met. Soc. China 29(2019) 2667-2676

Dynamic response pattern of gold prices to economic policy uncertainty

Gao CHAI1, Da-ming YOU1, Jin-yu CHEN1,2

1. School of Business, Central South University, Changsha 410083, China;

2. Institute of Metal Resources Strategy, Central South University, Changsha 410083, China

Received 23 April 2019; accepted 16 October 2019

Abstract:

Based on a time-varying parameter structural vector autoregression with stochastic volatility (TVP-SVAR-SV) model, the time-varying effects and country differences of economic policy uncertainty (EPU) on gold prices from August 2006 to December 2017 were examined. The results show that the effects of global economic policy uncertainty (GEPU) shock on gold prices change over time. The changes were positive during 2006-2008 and 2013-2017, while the impacts were negative during 2009-2012, implying that the efficiency of gold as a safe haven is not stable and depends on economic conditions. There are significant country differences regarding the impact of EPU on the price of gold, particularly during the international financial crisis, European debt crisis and Trump election. During the international financial crisis, EPU exerts a positive impact on gold prices in most countries. During the European debt crisis, the impact of EPU on gold prices is mainly negative in the examined countries. While during the Trump election, the impact displays positive and negative alternating in most countries.

Key words:

economic policy uncertainty; gold price; time-varying effects; TVP-SVAR-SV model;

1 Introduction

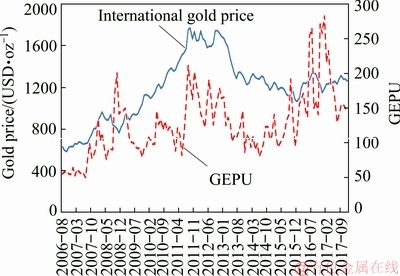

Economic policy is a combination of monetary, fiscal, and regulatory policy [1,2], and all of these policies need frequent adjustment. The uncertainty caused by change is termed economic policy uncertainty (EPU), and it plays an important role in commodity pricing [3-5]. As a special commodity, gold is considered a tool for hedging against economic policy risk and market turmoil [6-10]. Figure 1 shows that when there is a sharp rise in global economic policy uncertainty (GEPU) (e.g., during the international financial crisis of 2008-2009), the uncertainty triggers an increase in international gold prices. Therefore, changes in EPU may be a fundamental driver of gold prices, and it is necessary to incorporate EPU into the framework for gold price volatility. The study of the effects of EPU on gold prices could explain the reasons for turmoil in the gold market and provide a basis for investment decision making and macro control.

The existing literature focuses on the hedge and safe haven property of gold in times of market turmoil and economic crisis. SHAFIEE and TOPAL [11] investigated the influencing factors of gold prices and found that one of the key factors of rising gold prices was that during periods of financial market instability, gold played a safe-haven role against sharp fluctuations in traditional asset prices. BIALKOWSKI et al [12], van HOANG et al [13] and LAU et al [14] also concluded that gold was a safe haven asset during the panic period. YIN and LIU [15] noted that during the 1988 Latin American economic crisis, 1997 Asian financial crisis, 2000 Internet bubble, and 2008 global financial crisis, gold acted efficiently as a safe haven against the turmoil in the real economy. However, some of the recent literature has argued the safe haven property of gold [16]. For example, BAUR and MCDERMOTT [17] showed that gold was not a hedge and a safe haven for the stock markets of Australia, Canada, Japan, and large emerging markets such as the BRIC countries. Similarly, REBOREDO and JUAN [18] noted that gold could not hedge against oil price volatility.

Due to significant investor attraction to gold in times of high economic policy risk, an increasing number of scholars pay attention to the effects of EPU measures on gold prices [19,20]. JONES and SACKLEY [21] found that substantial EPU led to an increase in gold prices. Similarly, BALCILAR et al [8] showed that uncertainty measures had significant effects on gold returns and volatility for daily and monthly data while, for quarterly data, the effect was significant only for gold volatility. LI and LUCEY [22] noted that EPU was found to be a positive and robust determinant of a precious metal acting as a safe haven. BOUOIYOUR et al [10] found that there was a significant positive correlation between uncertainty and gold returns when uncertainty reached a peak. RAZA et al [2] suggested that EPU influenced gold prices in all the examined countries (Canada, China, France, Germany, Japan, Korea, the United Kingdom, and the United States), particularly at the low tails.

Fig. 1 Trend of international gold prices and GEPU

Although a substantial number of studies have examined the role of EPU measures on gold prices, there are two shortcomings in the previous studies. First, the existing research is mainly from a static and linear perspective and mainly uses vector autoregression (VAR) and structural vector autoregression (SVAR), which assume that the relationship between EPU and gold prices does not change over time. Second, there is a lack of studies on the heterogeneous impacts of EPU on the prices of gold across countries. Because of the remarkable differences in terms of policy interventions, economic reforms, and financial regulation activities [23], there may be differences in the responses of gold prices to EPU in different countries.

Based on the decomposition framework proposed by KILIAN [24], an SVAR model is used to decompose the structural shocks of international gold price fluctuations from 2006 to 2017 into four types: EPU shock, supply shock, demand shock, and speculation shock. Then, the TVP-SVAR-SV model is further used to investigate the time-varying features of EPU on gold prices at both the global and country levels. Compared with the existing literature, this work has two main contributions. First, based on a dynamic and nonlinear perspective, we extend the KILIAN methodology [24] by incorporating EPU into the structural gold price shocks system. We capture the time-varying effects of GEPU on gold prices and simulate the differences in the impact of GEPU on gold prices in different periods. Second, using the national EPU indices for 20 countries, the heterogeneous impacts of EPU on gold prices across countries are examined, which can provide more comprehensive empirical evidence to effectively assess the ability of gold to hedge against EPU.

2 Data and empirical methodology

2.1 Data specifications

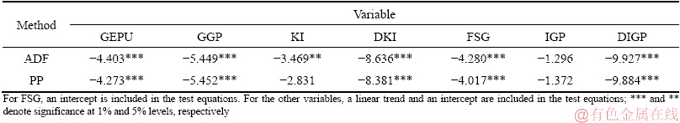

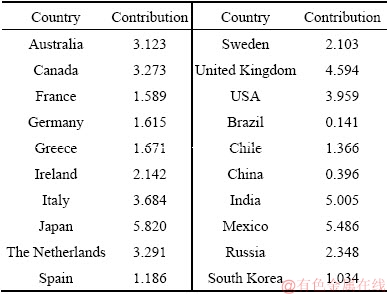

Our dataset is composed of monthly data on EPU, gold supply, gold demand, financial speculation, and international gold prices for the period from August 2006 to December 2017. To reflect the change in EPU, following WANG et al [25], BAKER et al [26], and BALLI et al [27], we select the GEPU index and national EPU indices for 13 developed countries (Australia, Canada, France, Germany, Greece, Ireland, Italy, Japan, the Netherlands, Spain, Sweden, the United Kingdom, and the United States) and seven developing countries (Brazil, Chile, China, India, Mexico, Russia, and South Korea). For the gold supply variable, we use global gold production (GGP). We use the monthly Kilian economic index (KI) developed in Ref. [24] to measure global demand. According to CHEN et al [28], the change in financial speculation is measured by the proportion of net long positions of non-commercial traders in gold futures (FSG). Following RAZA et al [2], we use the international gold prices (IGP) reported by the World Gold Council. To eliminate heteroscedasticity, we transform all the variables except KI and FSG into logarithmic values. Following WEI and GUO [29] and CHEN et al [30], we use the augmented Dicky–Fuller (ADF) and the Phillips and Perron (PP) tests to check the stationarity of the variables, and the results (Table 1) show that at the 5% significance level, the variables, GEPU, GGP and FSG, are stationary while the variables KI and IGP are stationary in terms of first differences (recorded as DKI and DIGP, respectively).

2.2 TVP-SVAR-SV model

Table 1 Results of unit root tests

Before constructing the TVP-SVAR-SV model to investigate the time-varying effects of EPU on gold prices, we extend the KILIAN methodology [24] by incorporating the EPU into the SVAR analysis framework and decompose the structural shocks of international gold price fluctuations into four types: EPU shock, supply shock, demand shock, and speculation shock. We construct an SVAR model of five variables as follows:

(1)

(1)

where yt=(EPUt, GGPt, DKIt, FSGt, DIGPt)′, β0 and βi are 5×5 matrices of coefficients, and εt is the structural shock vector.

Assuming A is reversible, we multiply matrix A-1 in Eq. (1) and derive the reduced-form VAR model:

(2)

(2)

where et is the disturbance term, and et=A-1εt. Then, we impose restrictions on A-1 to identify the SVAR model, and the restrictions on A-1 are based on KILIAN [24], KILIAN and MURPHY [31], CHEN et al [28], and HU et al [32]. We assume that the change in EPU is only due to the outbreak of economic policy risk and will not be contemporaneously affected by any shock. The errors et of the reduced form are described as

(3)

(3)

Based on the SVAR model, this work also adopts a TVP-SVAR-SV model. In this model, we can fully capture the time-varying characteristics by setting time-varying parameters in the SVAR model.

According to PRIMICERI [33], OMORI et al [34], NAKAJIMA et al [35], and WEN et al [36] , Eq. (1) can be written in the following way:

(4)

(4)

where β is a (25i+5)×1 vector, Xt=Ii (yt-1, …, yt-i), and∑ is a 5×5 dimensional diagonal matrix with a diagonal of [σ1, σ2, …, σ5]. We incorporate the time factor into Eq. (4), and the TVP-SVAR-SV model is given by

(yt-1, …, yt-i), and∑ is a 5×5 dimensional diagonal matrix with a diagonal of [σ1, σ2, …, σ5]. We incorporate the time factor into Eq. (4), and the TVP-SVAR-SV model is given by

(5)

(5)

Equation (5) forms the observation equation of the TVP-SVAR-SV model. Following PRIMICERI [33], NAKAJIMA et al [35], and JEBABLI et al [37], the parameters are supposed to follow a random walk process as follows:

(6)

(6)

with ht=(h1t, h2t, h3t, h4t, h5t)′ where hjt= , j=1, …, 5 and t=s+1,

, j=1, …, 5 and t=s+1, , n.

, n.

(7)

(7)

The variance covariance matrix of the model’s innovations is block diagonal:

(8)

(8)

where ,

, and

and  are assumed to be diagonal matrices.

are assumed to be diagonal matrices.

Following PRIMICERI [33], GONG and LIN [38], and WEN et al [39,40], we use Bayesian inference to estimate the TVP-SVAR-SV model using the Markov Chain Monte Carlo (MCMC) method. To obtain the estimated posterior, we adopt the Gibbs sampling algorithm described in Ref. [33] to discard the first 1000 as burn in and then draw 10000 samples.

3 Empirical results

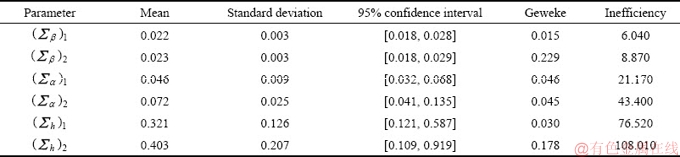

3.1 Estimation of selected parameters

We first study the time-varying effects of GEPU on international gold prices. We establish a TVP-SVAR-SV model whose lag length is set to be 1 based on Akaike information criterion (AIC) and Schwarz information criterion (SC). Table 2 gives the estimated results of selected parameters. The posterior means of the parameters are within the 95% confidence interval. The results of Geweke convergence diagnostics statistics are within the critical value of 5%; thus, the null hypothesis for the convergence of the posterior distribution cannot be rejected. In addition, the inefficiency factors of selected parameters are less than 100 (only one is more than 100), which is valid in MCMC samples with a total of 10000 samples. Overall, the estimation results suggest that the posterior draws efficiently [35,36,38,39,41].

3.2 Time-varying responses of gold prices to EPU at global level

Table 2 Estimation of selected parameters in TVP-SVAR-SV model

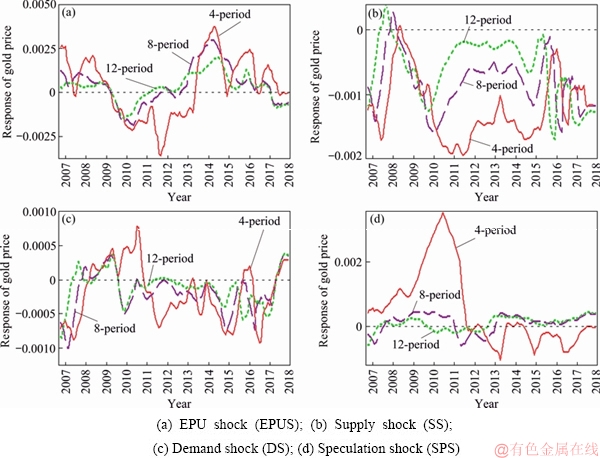

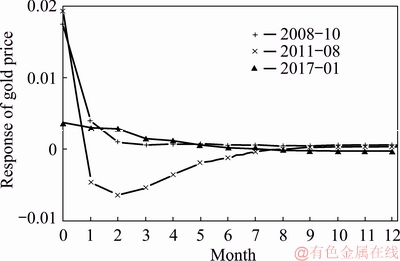

Fig. 2 Time-varying responses of gold prices to different structural shocks

Figure 2 presents the uniformly-spaced impulse response trajectories of international gold prices to structural shocks for four, eight, and 12-month lag periods. As shown, the effects of the EPU shock on gold prices changed over time and were positive for the periods from 2006 to 2008 and from 2013 to 2017, reaching a peak of 0.0038 in mid-2014. However, the impacts were negative during the period from 2009 to 2012. In summary, an increase in EPU increases the price of gold in most cases, implying that gold performs well as a safe haven against economic policy risk, while the efficiency of gold as a safe haven is not stable and depends on economic conditions [15]. This is because different EPU events (e.g., economic environment change, macro policy promulgation, economic crisis, and market turbulence) have different effects on the gold market. The impact of a single event can be positive or negative, and multiple EPU events often coexist at the same time point influencing the gold market simultaneously and eventually forming complex and changeable effects [42]. In addition, in terms of different lag periods, EPU shock has the most significant impact on international gold prices for the four-month lag period, followed by the eight-month lag period, while the impact is minimal for the 12-month lag period. This result shows that the impact of EPU on gold prices varies for different lag periods and, as the duration of the lag increases, the impact gradually weakens. This finding implies that the gold market can be effectively adjusted over time to mitigate the shock effect and ensure price stability [43].

In terms of other structural shocks, the effects of supply shocks on gold prices were negative during the sample period and reached a low of -0.002 in 2011. This result is consistent with that of GAO and GU [44]. Following a shock to global demand, the responses of gold prices were mostly negative, and a positive impact only appeared during 2008-2009, which implies that the pull effects of economic demand on gold prices are insignificant. In addition, the impact of speculation shocks on gold prices was only significant in the short term and were positive and large before 2011. The impact then turns negative and small from 2012 to 2017. This result is partly in line with that of MING et al [45], who found that the gold price series was affected by speculation in one year.

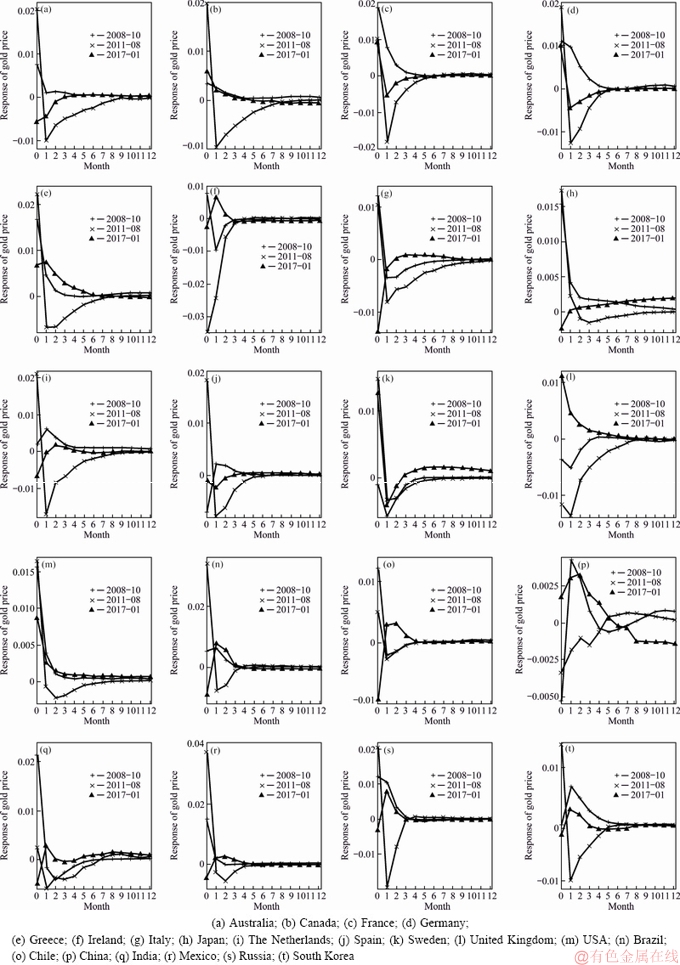

Figure 1 shows that there are three peaks (i.e., October 2008, August 2011, and January 2017) in GEPU fluctuations. To show the differential effects of the EPU shock on gold prices at different time points, we select three time points to analyze the differences. The time points 2008-10, 2011-08 and 2017-01 capture the outbreak of the international financial crisis, the European debt crisis, and the Trump election, respectively. During the three periods, the change in the economic environment affected economic development severely and increased EPU. The changes directly or indirectly affected the expectations and behavior of the participants in the gold market as well as regulation and control of the gold market by policy makers. These factors, in turn, affected the supply and demand of gold, ultimately causing gold price fluctuations. Figure 3 shows that during the international financial crisis, a shock to GEPU caused an immediate positive response in gold prices in the current period with response reaching a peak of 0.017. Then, the response declined rapidly and lasted for approximately two months. During the European debt crisis, we find that the responses of gold prices to GEPU shocks were positive in the current period but turned negative in the first month with the response reaching a bottom of -0.006 in the second month. Then, the negative response declined gradually and disappeared in approximately eight months. During the Trump election, the response of gold prices was positive in the current period and reached a peak of 0.004, and then the response declined gradually and lasted approximately five months. These results show that during these three periods, the responses of gold prices to GEPU occurred quickly and reached a peak in the current period. With respect to gold investors, when the EPU events occurred during the economic crisis and amidst market turmoil, the investment expectations of investors were directly affected, changed current investment behavior, and affected the gold prices. Thus, the rate of response was rapid. However, there were significant differences in the direction and duration of responses for different time periods. Specifically, during the international financial crisis and Trump election, GEPU had a positive impact on gold prices, while during the European debt crisis, the impact of GEPU on gold prices was mostly negative and longer lasting. The reason for this difference is that unlike the international financial crisis and Trump election, when the gold market was shocked by the European debt crisis, the gold prices had been at a high level for a long time. Consumer demand fell more rapidly at this time, placing downward pressure on gold prices.

Fig. 3 Impulse responses of gold prices to EPU at different time periods

3.3 Heterogeneous responses of gold prices to EPU across countries

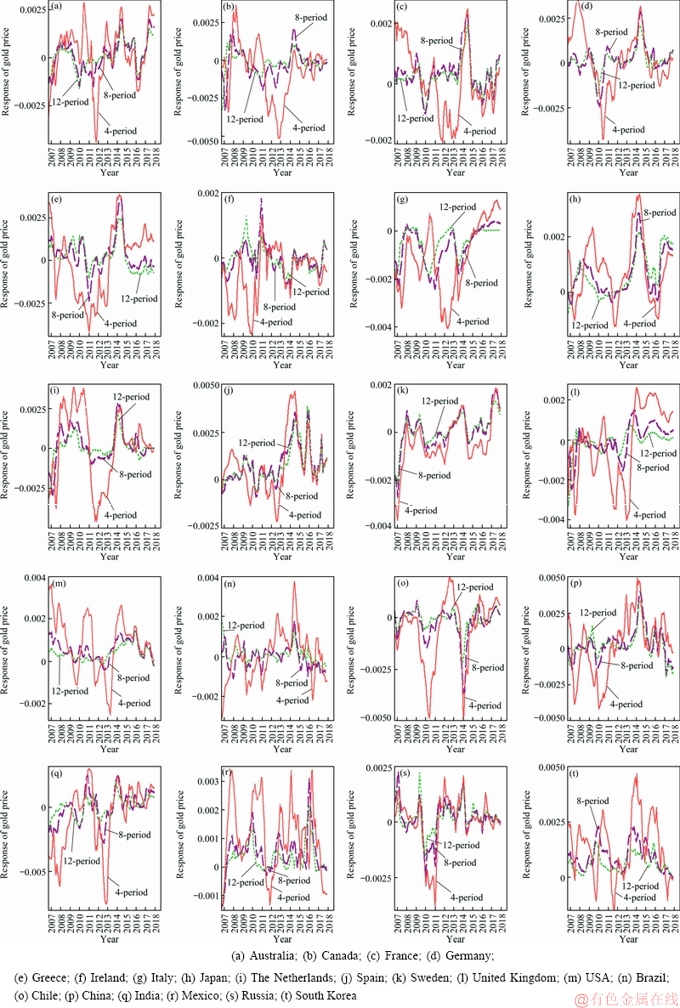

Fig. 4 Time-varying responses of gold prices to EPU in different countries

We compare the heterogeneous impacts of EPU in different countries on gold prices. Figure 4 shows that the effects of EPU on gold prices are mainly positive in all countries except Canada, Ireland, Italy, Sweden and Chile, and the time-varying responses of gold prices to EPU in different countries appear diverse. This is because different countries present remarkable differences in terms of economic development, gold production and consumption, attention to policy, and risk preference. Compared with developed countries, the responses of gold prices are more volatile in developing countries. This phenomenon is particularly significant in China. In 2010, negative responses reached the lowest of -0.0038; however, the shock effects rebounded rapidly and reached a positive maximum of 0.0050 in mid-2014. This result reflects the instability and inconsistency of China’s economic policies and does not provide gold investors with a high level of assurance.

In addition, the responses at three different time points displayed significant differences, as shown in Fig. 5.

Fig. 5 Time-varying responses of gold prices to EPU at different time periods

Specifically, during the international financial crisis, the impact of EPU on gold prices was positive in most countries, and the impact was relatively large in the United States, France, Greece, Japan, and Mexico compared with other countries. In the United States, after the global financial crisis emerged, the Fed cut the federal funds rate 10 times in efforts to stimulate domestic investment and consumption. These actions caused residents to withdraw assets from bank savings and invest them in the stock market and futures market. The inflow of funds to the gold market pushed up gold prices. However, in countries such as Sweden and the United Kingdom, the increase in EPU led to a decrease in gold prices. This decrease implies that gold acts inefficiently as a safe haven against economic policy risk in these countries. During the European debt crisis, the responses of gold prices to EPU were mainly negative in 20 countries, and among them, the negative responses were most significant in Ireland and the United Kingdom. This result could be explained by the strong financial risk impact that the European debt crisis exerted on these two countries [46]. However, during the Trump election, the impacts of EPU on gold prices displayed positive and negative alternating in most countries, and were weaker compared with the remaining two periods.

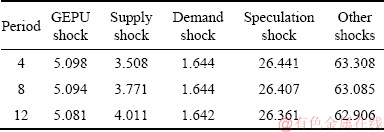

3.4 Relative importance of EPU influence on gold prices

To quantify the relative importance of EPU on gold prices, we use variance decomposition for further analysis. Table 3 gives the contributions of structural shocks to fluctuations in gold prices. When the variance decomposition results reach a stable state in the long term (12 months), we see that the contribution of GEPU shocks to fluctuations in gold prices is 5.081%, ranking second among the four gold price influencing factors, while speculation shocks (26.361%) contribute most to fluctuations in gold prices. These findings are consistent with those of MUTAFOGLU et al [47], who found that positions held by non-commercial and non-reporting traders were a positive determinant of gold prices. BOSCH and PRADKHAN [48] also reached a similar conclusion based on an examination of the linkage between speculation shocks and gold prices.

Table 3 Contributions of structural shocks to fluctuations in gold prices (%)

Table 4 Contributions of EPU shocks to fluctuations in gold prices across countries (%)

In addition, contributions are relatively high in most developed countries (Table 4), and the average contribution of developed countries (2.93%) is higher than that of developing countries (2.25%). This is mainly due to the larger share of global GDP and policy influence in developed countries. We observe that the contribution (5.820%) of Japan’s EPU to gold prices is the largest. For developing countries such as China (0.396%) and Brazil (0.141%), the contributions are almost negligible. This result is surprising. China is the largest gold producer and consumer in the world, according to China Gold Association. In 2017, China’s total gold production was 426 t, and the actual consumption of gold was 1089 t. However, China’s huge supply and demand has not created a market advantage [49], and the gold futures market is relatively immature with the result that China’s EPU has minimal impact on international gold prices.

4 Conclusions

(1) The effects of GEPU shocks on gold prices changed over time and were positive for the periods from 2006 to 2008 and from 2013 to 2017. However, the impacts were negative for the period from 2009 to 2012, implying that the efficiency of gold as a safe haven is not stable and depends on economic conditions. Interestingly, the impact of EPU on gold prices varies for different lag periods. As the duration of the lag increases, the impact gradually weakens.

(2) The responses of gold prices to EPU become greater in times of major economic crisis and market turbulence. This is particularly the case during the international financial crisis, European debt crisis, and Trump election. During the international financial crisis and Trump election, GEPU had a positive impact on gold prices, while during the European debt crisis, the impact of GEPU on gold prices was mostly negative and longer lasting. In addition, there are significant country differences in the effect of EPU on gold prices. Compared with developed countries, the responses of gold prices are more volatile of EPU shock in developing countries. Among 20 countries, the influence of Japan’s EPU on gold prices is the largest. These findings provide new insights into the relationship between EPU and gold price dynamics.

References

[1] ADJEI F A, ADJEI M. Economic policy uncertainty, market returns, and expected return predictability [J]. Journal of Financial Economic Policy, 2017, 9(3): 1-29.

[2] RAZA S A, SHAH N, SHAHBAZ M. Does economic policy uncertainty influence gold prices? Evidence from a nonparametric causality-in-quantiles approach [J]. Resources Policy, 2018, 57: 61-68.

[3] GONG X, LIN B. Forecasting the good and bad uncertainties of crude oil prices using a HAR framework [J]. Energy Economics, 2017, 67: 315-327.

[4] XIAO J, ZHOU M, WEN F, WEN F. Asymmetric impacts of oil price uncertainty on Chinese stock returns under different market conditions: Evidence from oil volatility index [J]. Energy Economics, 2018, 74: 777-786.

[5] XIAO J, HU C, OUYANG G, WEN F. Impacts of oil implied volatility shocks on stock implied volatility in China: Empirical evidence from a quantile regression approach [J]. Energy Economics, 2019, 80: 297-309.

[6] HARTMANN P, STRAETMANS S, VRIES C D. Asset market linkages in crisis periods [J]. Review of Economics and Statistics, 2004, 86(1): 313-326.

[7] O'CONNOR F A, LUCEY B M, BATTEN J A, BAUR D G. The financial economics of gold—A survey [J]. International Review of Financial Analysis, 2015, 41: 186-205.

[8] BALCILAR M, GUPTA R, PIERDZIOCH C. Does uncertainty move the gold price? New evidence from a nonparametric causality-in- quantiles test [J]. Resources Policy, 2016, 49: 74-80.

[9] BILGIN M H, GOZGOR G, LAU C K M, SHENG X. The effects of uncertainty measures on the price of gold [J]. International Review of Financial Analysis, 2018, 58: 1-7.

[10] BOUOIYOUR J, SELMI R, WOHAR M E. Measuring the response of gold prices to uncertainty: An analysis beyond the mean [J]. Economic Modelling, 2018, 75: 105-116.

[11] SHAFIEE S, TOPAL E. An overview of global gold market and gold price forecasting [J]. Resources Policy, 2010, 35(3): 178-189.

[12] BIALKOWSKI J, BOHL M T, STEPHAN P M, WISNIEWSKI T P. The gold price in times of crisis [J]. International Review of Financial Analysis, 2015, 41: 329-339.

[13] van HOANG T H, LAHIANI A, HELLER D. Is gold a hedge against inflation? New evidence from a nonlinear ARDL approach [J]. Economic Modelling, 2016, 54: 54-66.

[14] LAU M C K, VIGNE S A, WANG S, YAROVAYA L. Return spillovers between white precious metal ETFs: The role of oil, gold, and global equity [J]. International Review of Financial Analysis, 2017, 52: 316-332.

[15] YIN L, LIU Y. Is gold a stable safe-haven asset? —Based on the perspective of macroeconomic uncertainty [J]. Studies of International Finance, 2015, 339(7): 87-96 (in Chinese).

[16] BAUR D G, LUCEY B M. Is gold a hedge or a safe haven? An analysis of stocks, bonds and gold [J]. Financial Review, 2010, 45(2): 217-229.

[17] BAUR D G, MCDERMOTT T K. Is gold a safe haven? International evidence [J]. Journal of Banking & Finance, 2010, 34(8): 1886-1898.

[18] REBOREDO, JUAN C. Is gold a hedge or safe haven against oil price movements? [J]. Resources Policy, 2013, 38(2): 130-137.

[19] GAO R, ZHANG B. How does economic policy uncertainty drive gold–stock correlations? Evidence from the UK [J]. Applied Economics, 2016, 48(33): 3081-3087.

[20] ZHOU Y, HAN L, YIN L. Is the relationship between gold and the US dollar always negative? the role of macroeconomic uncertainty [J]. Applied Economics, 2018, 50(4): 354-370.

[21] JONES A T, SACKLEY W H. An uncertain suggestion for gold-pricing models: The effect of economic policy uncertainty on gold prices [J]. Journal of Economics and Finance, 2016, 40(2): 367-379.

[22] LI S, LUCEY B M. Reassessing the role of precious metals as safe havens–What colour is your haven and why? [J]. Journal of Commodity Markets, 2017, 7: 1-14.

[23] BASTIANIN A, CONTI F, MANERA M. The impacts of oil price shocks on stock market volatility: Evidence from the G7 countries [J]. Energy Policy, 2016, 98: 160-169.

[24] KILIAN L. Not all oil price shocks are alike: Disentangling demand and supply shocks in the crude oil market [J]. American Economic Review, 2009, 99(3): 1053-1069.

[25] WANG Y, ZHANG B, DIAO X, WU C. Commodity price changes and the predictability of economic policy uncertainty [J]. Economics Letters, 2015, 127: 39-42.

[26] BAKER S R, BLOOM N, DAVIS S J. Measuring economic policy uncertainty [J]. The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 2016, 131(4): 1593-1636.

[27] BALLI F, UDDIN G S, MUDASSAR H, YOON S M. Cross-country determinants of economic policy uncertainty spillovers [J]. Economics Letters, 2017, 156: 179-183.

[28] CHEN H, LIAO H, TANG B J, WEI Y M. Impacts of OPEC’s political risk on the international crude oil prices: An empirical analysis based on the SVAR models [J]. Energy Economics, 2016, 57: 42-49.

[29] WEI Y, GUO X. An empirical analysis of the relationship between oil prices and the Chinese macro-economy [J]. Energy Economics, 2016, 56: 88-100.

[30] CHEN J, ZHU X, ZHONG M. Nonlinear effects of financial factors on fluctuations in nonferrous metals prices: A Markov-switching VAR analysis [J]. Resources Policy, 2019, 61: 489-500.

[31] KILIAN L, MURPHY D P. The role of inventories and speculative trading in the global market for crude oil [J]. Journal of Applied Econometrics, 2014, 29(3): 454-478.

[32] HU C, LIU X, PAN B, SHENG H, ZHONG M, ZHU X, WEN F. The impact of international price shocks on China’s nonferrous metal companies: A case study of copper [J]. Journal of Cleaner Production, 2017, 168: 254-262.

[33] PRIMICERI G E. Time varying structural vector autoregressions and monetary policy [J]. The Review of Economic Studies, 2005, 72(3): 821-852.

[34] OMORI Y, CHIB S, SHEPHARD N, NAKAJIMA J. Stochastic volatility with leverage: Fast and efficient likelihood inference [J]. Journal of Econometrics, 2007, 140(2): 425-449.

[35] NAKAJIMA J, KASUYA M, WATANABE T. Bayesian analysis of time-varying parameter vector autoregressive model for the Japanese economy and monetary policy [J]. Journal of the Japanese and International Economies, 2011, 25(3): 225-245.

[36] WEN F, ZHAO C, HU C. Time-varying effects of international copper price shocks on China’s producer price index [J]. Resources Policy, 2019, 62: 507-514.

[37] JEBABLI I, AROURI M, FREDERIC T. On the effects of world stock market and oil price shocks on food prices: An empirical investigation based on TVP-VAR models with stochastic volatility [J]. Energy Economics, 2014, 45: 66-98.

[38] GONG X, LIN B. Time-varying effects of oil supply and demand shocks on China’s macro-economy [J]. Energy, 2018, 149: 424-437.

[39] WEN F, MIN F, ZHANG Y J, YANG C. Crude oil price shocks, monetary policy, and China’s economy [J]. International Journal of Finance & Economics, 2019, 24(2): 812-827.

[40] WEN F, XIAO J, HUANG C, XIA X. Interaction between oil and US dollar exchange rate: Nonlinear causality, time-varying influence and structural breaks in volatility [J]. Applied Economics, 2018c, 50(3): 319-334.

[41] ZHONG M, HE R, CHEN J, HUANG J. Time-varying effects of international nonferrous metal price shocks on China’s industrial economy [J]. Physica A: Statistical Mechanics and its Applications, 2019, 528(15): 1-14.

[42] PASTOR L’, VERONESI P. Political uncertainty and risk premia [J]. Journal of Financial Economics, 2013, 110(3): 520-545.

[43] SHI Z Z, WANG M L, HU X D. Economic policy uncertainty and price fluctuation of animal products in China [J]. Chinese Rural Economy, 2016, 8: 42-55 (in Chinese).

[44] GAO F, GU W Y. An analysis on the influencing factors of international gold price: Perspective of the dual nature of gold as a commodity and as a value guarantee [J]. China Soft Science, 2018, 5: 160-170 (in Chinese).

[45] MING L, YANG S, CHENG C. The double nature of the price of gold—A quantitative analysis based on Ensemble Empirical Mode Decomposition [J]. Resources Policy, 2016, 47: 125-131.

[46] LEE C C, LEE C C, NING S L. Dynamic relationship of oil price shocks and country risks [J]. Energy Economics, 2017, 66: 571-581.

[47] MUTAFOGLU T H, TOKAT E, TOKAT H A. Forecasting precious metal price movements using trader positions [J]. Resources Policy, 2012, 37(3): 273-280.

[48] BOSCH D, PRADKHAN E. The impact of speculation on precious metals futures markets [J]. Resources Policy, 2015, 44: 118-134.

[49] ZHU X H, CHEN J Y, ZHONG M R. Dynamic interacting relationships among international oil prices, macroeconomic variables and precious metal prices [J]. Transactions of Nonferrous Metals Society of China, 2015, 25(2): 669-676.

黄金价格对经济政策不确定性冲击的动态响应模式

柴 杲1,游达明1,谌金宇1,2

1. 中南大学 商学院,长沙 410083;

2. 中南大学 金属资源战略研究院,长沙 410083

摘 要:基于带有随机波动率的时变参数结构向量自回归模型(TVP-SVAR-SV),采用2006年8月至2017年12月的月度数据,考察经济政策不确定性对黄金价格的时变效应及国别差异。结果表明:全球经济政策不确定性冲击对黄金价格的影响随着时间推移而变化。动态冲击效应在2006~2008年以及2013~2017年更多表现为正向影响,而在2009~2012年则主要为负,显示黄金的避险能力并不稳定,因时而异。此外,经济政策不确定性对黄金价格的冲击效应具有显著的国别差异,尤其是在2008年国际金融危机、2011年欧债危机以及2017年特朗普就任美国总统3个时期。在国际金融危机时期,大多数国家的经济政策不确定性对黄金价格的冲击具有正向影响;在欧债危机时期,样本国家的经济政策不确定性对黄金价格的影响主要为负;而在特朗普就任美国总统时期,冲击效应在大多数国家呈正负交替态势。

关键词:经济政策不确定性;黄金价格;时变影响;TVP-SVAR-SV模型

(Edited by Bing YANG)

Foundation item: Projects (71633006, 71874210, 71874207, 71573282) supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China

Corresponding author: Jin-yu CHEN; Tel: +86-15802548455; E-mail: cjy2014@csu.edu.cn

DOI: 10.1016/S1003-6326(19)65173-3

Abstract: Based on a time-varying parameter structural vector autoregression with stochastic volatility (TVP-SVAR-SV) model, the time-varying effects and country differences of economic policy uncertainty (EPU) on gold prices from August 2006 to December 2017 were examined. The results show that the effects of global economic policy uncertainty (GEPU) shock on gold prices change over time. The changes were positive during 2006-2008 and 2013-2017, while the impacts were negative during 2009-2012, implying that the efficiency of gold as a safe haven is not stable and depends on economic conditions. There are significant country differences regarding the impact of EPU on the price of gold, particularly during the international financial crisis, European debt crisis and Trump election. During the international financial crisis, EPU exerts a positive impact on gold prices in most countries. During the European debt crisis, the impact of EPU on gold prices is mainly negative in the examined countries. While during the Trump election, the impact displays positive and negative alternating in most countries.