Expression, purification and molecular modeling of iron-containing superoxide dismutase from Acidithiobacillus ferrooxidans

LIU Yuan-dong(刘元东)1, GAO Jian(高 建)2, QIU Guan-zhou(邱冠周)1, LIU Xue-duan(刘学端)1,

ZHANG Cheng-gui(张成桂)1, OUYANG Xu-dong(欧阳叙东)1, JIANG Ying(蒋 莹)1, ZENG Jia(曾 佳)1

1. School of Minerals Processing and Bioengineering, Central South University, Changsha 410083, China;

2. School of Life Science, Hunan University of Science and Technology, Xiangtan 411201, China

Received 20 September 2008; accepted 5 November 2008

Abstract: The superoxide dismutase(SOD) from Acidithiobacillus ferrooxidans may play an important role in its tolerance to the extremely toxic and oxidative environment of bioleaching. This gene was cloned and then successfully expressed in Escherichia coli. The expressed protein was finally purified by one-step affinity chromatography to homogeneity and observed to be dimer according to SDS-PAGE and MALDI-TOF-MS. The metal content determination and optical spectra results of the recombinant protein confirmed that the protein was an iron-containing superoxide dismutase. Molecular modeling for the protein revealed that the iron atom was ligated by His26, His75, Asp158 and His162.

Key words: Acidithiobacillus ferrooxidans; superoxide dismutase; expression; purification; molecular modeling; His-tag

1 Introduction

Superoxide dismutase (SOD, EC:1.15.1.1) catalyses the conversion of superoxide radicals to molecular oxygen and hydrogen peroxide to protect organisms against toxic radicals produced during oxidative processes[1]. It is widely used in clinical treatment, food, and cosmetic industry for its important physiologic function[2-3]. The global analysis of cellular factors and responses involved in Pseudomonas aeruginosa resistant to arsenite indicates that the SOD is essential for non-efflux-based mechanisms of arsenic detoxification, in which its function is in the protection of superoxide-sensitive sulfhydryl groups[4]. The studies of superoxide dismutases protecting Escherichia coli from heavy metal toxicity[5] and superoxide dismutases of heavy metal resistant streptomycetes[6] suggest that SOD is also important for resistance to heavy metals. SODs can be divided into four distinct classes, Cu/Zn, Fe, Mn and Ni according to their active prosthetic group contained[7]. Among them, Fe SODs are generally found in prokaryotes, where some proteins from various sources are characterized[8-10] and several structures from various sources are resolved[11-13].

Acidithiobacillus ferrooxidans, a Gram-negative and chemolithotrophic bacterium, is one of the most extensively studied bacteria in bioleaching and acidic mine drainage, which are extremely acidic and contain a large range of high concentration of toxic heavy cations and oxyanions[14]. A. ferrooxidans can not only survive in those poisonous surroundings, but also take advantage of these conditions to gain energy for growth through oxidizing ferrous ion. It can also reduce sulfur compounds as well as convert the insoluble metal sulfides to their soluble metal sulfates[15]. This capability is therefore utilized to extract metals such as copper, zinc, uranium, and gold from minerals in industry[16]. So, understanding the anti-toxicity mechanism of A. ferrooxidans is of vital importance from economic, scientific and environmental point of view.

It was reported that the genome sequence of A. ferrooxidans ATCC 23270 includes a sod gene which may encode the SOD, so the gene may play an important role in its tolerance to the extremely toxic and oxidative environment of bioleaching. But till now, less experimental and theoretical efforts were made in the protein encoded by the gene from this species and its three-dimensional(3D) structure remained to be elucidated. Knowledges of the characteristic and detailed 3D structure of it are, however, essential for understanding its catalytic mechanism and function in the unique physiology of A. ferrooxidans.

In this work, the gene sod from A. ferrooxidans Fe-1 was cloned and expressed in E. coli, finally purified by one-step affinity chromatography. With homology modeling techniques and molecular dynamic simulations, a reliable 3D molecular structure of the protein encoded by this gene was also built.

2 Experimental

2.1 Materials

Acidithiobacillus ferrooxidans Fe-1 was isolated, which was identified to be identical with previous report by genomic DNA sequence analysis. A HiTrap chelating metal affinity column was purchased from GE healthcare LTD. The pET-28a (+) vectors and E. coli strain BL21 (DE3) competent cells came from Invitrogen Life Technologies. The Plasmid Mini kit and the E.Z.N.ATM Gel Extraction kit were obtained from Omega BIO-TEK Inc. (USA). Oligonucleotides were synthesized by Sangon Company of Shanghai, China. Taq DNA polymerase came from MBI Fermentas, Germany. T4 DNA ligase and restriction enzymes were purchased from New England Biolabs, America. All other reagents were of research grade or better and obtained from commercial sources.

2.2 Cloning of sod gene from A. ferrooxidans

Genomic DNA from A. ferrooxidans Fe-1 was prepared using the EZ-10 spin column genomic DNA isolation kit from Bio Basic Inc., following the manufacturer’s instructions for bacterial DNA extraction. This genomic DNA was used as a template for polymerase chain reaction(PCR). The gene was amplified by PCR using primers that were designed to add six continuous histidine codons to 5′-primer. The sequence of the forward primer was (5′-CCCTTGGATC- CATGTCCGAATATAGC-3′). The sequence of the reverse primer was (5′-CCCGGAAGCTTTCAGAAGC- GCTTGAAAATC-3′), which has a HindⅢ. PCR amplification was performed using Taq DNA polymerase, and samples were subjected to 28 cycles of 30 s of denaturation at 95 ℃, 40 s of annealing at 55 ℃, and 1 min of elongation at 72 ℃ in a Mastercycler Personal of Eppendorf Model made in Germany. The amplification products were analyzed by electrophoresis on a 1.0% agarose gel and stained with ethidium bromide. The resulting PCR product was gel purified, double digested and ligated into the double digested pET-28a (+) expression vector, resulting in the pET-28::SOD plasmid. The constructed pET-28::SOD plasmid was transformed into HB101 competent cells for screening purposes. The identified positive colony was grown in LB medium containing kanamycin (30 mg/L), and the plasmid pET-28::SOD was isolated from harvested bacteria cells using a plasmid extraction kit. The isolated pLM1::SOD pET-28::SOD plasmid was then transformed into E. coli strain BL21(DE3) competent cells for expression purposes.

2.3 Expression of soluble recombinant protein of SOD gene from A. ferrooxidans in E. coli

The E. coli strain BL21 (DE3) cells with pET::SOD plasmid was grown at 37 ℃ in 500 mL of TB medium containing ampicillin (100 mg/L) to an OD600 of 0.6. At this point, the cells were incubated at room temperature with the addition of 0.5 mmol/L IPTG with shaking at 180 r/min overnight. The cells were harvested by centrifugation and the cell pellet was washed with an equal volume of sterile water. The cells were again harvested by centrifugation, suspended in start buffer (20 mmol/L potassium phosphate, pH 7.4, 0.5 mol/L NaCl), incubated with 5 mg lysozyme at room temperature for 0.5 h, and then stored at 80 ℃ for purification.

2.4 Purification of SOD protein from A. ferrooxidans

The cells were lysed by sonication four times for 30 s each time using a 150-W Autotune Series High Intensity Ultrasonic Sonicator equipped with an 8 mm- diameter tip. The insoluble debris was removed by centrifugation and the clear supernatant was used for protein purification. The Hi-Trap column was first equilibrated with 0.1 mol/L nickel sulfate to charge the column with nickel ions followed by 5 column volumes of MiliQ water to remove unbound nickel ions from the column, and then by 5 column volumes of start buffer (20 mmol/L potassium phosphate, pH 7.4, 0.5 mol/L NaCl) to equilibrate the column. The clarified sample was applied to the Hi-Trap column after filtering through a 0.45 μm filter. The column was washed with 5 column volumes of start buffer followed with 5 column volumes of wash buffer (20 mmol/L potassium phosphate, pH 7.4, 0.5 mol/L NaCl, 50 mmol/L imidazole), and subsequently the protein was eluted with an elution buffer (20 mmol/L potassium phosphate, pH 7.4, 0.5 mol/L NaCl, 500 mmol/L imidazole). The method of BRADFORD[17] was used to determine the protein content with bovine serum albumin as the standard. The eluted fractions were analyzed by sodium dodecylsulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) with 18% of acrylamide according to LAEMMLI[18]. The gels were stained with Coomassie Brilliant Blue R-250. The purified enzyme fractions were combined and dialyzed against a 20 mmol/L potassium phosphate buffer, pH 6.0, 5% glycerol, and 5 mmol/L β-mercaptoethanol, and then stored in a -80 ℃ freezer.

2.5 MALDI-TOF-MS of SOD protein

The molecular mass of protein was determined using Ultraflex? TOF/TOF spectrometer (Bruker Daltonics) equipped with nitrogen laser (337 nm) and operated in reflector/delay extraction mode. An accelerating voltage of 25 kV was used. The MALDI- TOF-MS result was obtained in the linear positive mode using α-cyano-4-hydroxy-cinnamic acid (saturated solution in 50% acetonitrile with 0.1% trifluoroacetic acid) as the UV-absorbing matrix. Prior to MALDI-MS analysis, the protein sample was diluted to a concentration of approximately 1 μmol/L in 20 mmol/L potassium phosphate buffer containing 0.5 mol/L NaCl at pH 6.0. Spectra were recorded in positive-ion mode from m/z 2 500-15 000. Theoretical molecular mass was calculated by the Compute pI/Mw tool from Expasy Proteomics Server of the Swiss Institute of Bioinformatics(SIB).

2.6 Enzyme activity assays, metal content determina- tion and UV-vis scanning

SOD specific activity was determined using the standard xanthine oxidase/cytochrome c assay at pH 7.8 as described by McCORD and FRIDOVICH[19]. The increase in absorbance at 550 nm was recorded at 25 ℃ with a Beckman DU-640 spectrophotometer. SOD activity was also visualized in 7% nondenaturing polyacrylamide gel by nitroblue tetrazolium activity staining, as described by BEAUCHAMP and FRIDOVICH[20]. To perform the inhibition study, 5 mmol/L H2O2 was added during incubation in 2.45 mmol/L nitroblue tetrazolium(NBT)[21]. Metal contents were determined by inductively coupled plasma-atomic emission(ICP-AE) analysis using a Shimadzu ICPS-1000Ⅲ. UV-visible spectra scanning was carried out at 25 ℃ on a Techcomp UV-2300 spectro- photometer. The samples of SOD proteins (10 μmol/L) were prepared in 20 mmol/L phosphate buffer containing 0.5 mol/L NaCl at pH 6.0.

2.7 Molecular structure modeling of SOD protein

The primary amino acid sequence of the SOD was deduced from the DNA sequence of the cloned sod gene from A. ferrooxidans Fe-1. All simulations were performed on the Dell Precision 470 workstation with Redhat Linux system using Insight Ⅱ software package developed by Accelrys Software Inc.

The Homology module was used to build the initial model of this SOD. Firstly, a sequence similarity search on Protein Data Bank(PDB) by BLAST program was carried out to find the related protein structures as templates. Then, Modeler program was performed to build the 3D structure. The initial model was further improved by using Discover_3 module. The final structure was assessed by Profile-3D and ProStat programs.

3 Results and discussion

3.1 Cloning of SOD protein gene from Acidithiobacillus ferrooxidans

The initial transformation was carried out with HB101 competent cells for screening purposes because the transformation efficiency with HB101 competent cells is very high. The identified positive colony was grown in LB medium and the corresponding plasmid was isolated and re-transformed to E. coli BL21(DE3).

3.2 Expression and purification of SOD protein from A. ferrooxidans

The expression of SOD protein from A. ferrooxidans in E. coli BL21 (DE3) was carried out at different temperatures and IPTG concentrations, and proteins were obtained in all tested conditions. It was found that the protein expressed better at 0.5 mmol/L IPTG concentration and resulted in more soluble protein at room temperature (25 ℃) than at 37 ℃.

Nickel metal-affinity resin column was used for single step purification of His-tagged SOD protein. The eluted enzyme was observed to be a red-brown protein, indicating the Fe atom is still bound to protein after purification. The final protein yield after affinity chromatography is 3.2%, and T7 polymerase promoter/ BL21 (DE3) expression system is an ideal system for expressing the SOD protein in high yield. The leader peptide and hexahistag in the N-terminal may be responsible for the efficient expression of the SOD protein.

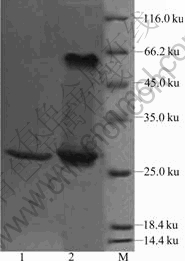

The purity of the enzyme was further examined by SDS-PAGE and two bands with apparent molecular masses of 27 and 60 ku were observed with >95% purity when the purified protein was incubated with LAEMMLI’s sample buffer overnight at 25 ℃ (Fig.1), which appeared to coincide with the calculated molecular masses for the SOD monomer and dimer, respectively. The boiled SOD protein showed a molecular mass of about 27 ku, which is in agreement with the deduced molecular mass of a monomer. Similar results were observed for Fe-SOD from a hot spring sample[8]. Thus, the SOD protein was observed to be dimer. The stability of the purified SOD protein was tested and the His-tagged protein was proved to be highly stable. The

Fig.1 SDS-PAGE of recombinant SOD protein from A. ferrooxidans (1—Purified SOD protein boiled in LAEMMLI’s sample buffer for 3 min; 2—Purified SOD protein incubated with LAEMMLI’s sample buffer overnight at 25 ℃; M—Molecular mass marker)

protein could be stored at 4 ℃ for one month without significant change of activity.

3.3 MALDI-TOF-MS of SOD protein

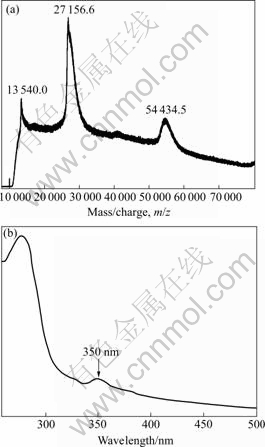

The MALDI-TOF-MS result of the recombinant SOD is shown in Fig.2(a). It can be seen that there are three major peaks. The 54 434.5 peak corresponds to the SOD dimer with 1 charge, the 27 156.6 peak corresponds to the SOD dimer with 2 charges or the SOD monomer with 1 charge, and the 13 540.0 peak corresponds to the SOD dimer with 4 charges or the SOD monomer with 2 charges. So, according to these results, the recombinant SOD protein was also proposed to be a dimer, which was not stable during the MS process and could easily form two identical monomers. This is in line with the above SDS-PAGE results. The protein sequence of the SOD protein with the His-tags and leader peptide in the N-terminal had a theoretical average molecular mass of 26 348.47 u, which was also in agreement with these experimental results.

3.4 Activity assays, metal content determination and UV-scanning of SOD protein

The purified protein exhibited a specific SOD activity of 1 690 U/mg by the xanthine oxidase/ cytochrome c assay, which was comparable with that of the recombinant Fe-SOD from a hot spring sample[8]. The purity of the enzyme also showed SOD activity by the NBT staining analysis. When being tested by adding H2O2 during incubation in NBT, the enzyme was sensitive to hydrogen peroxide, which inhibits Fe-SOD but does not inhibit Mn-SOD[21]. To quantify bound metals, ICP-AE analysis was performed, and the results indicated that the SOD contained 0.94 iron atoms per monomer, and none of manganese, copper, zinc and nickel was detected. The molar ratio of bound iron to the SOD was almost 1?1. Similar results were observed for Fe-SOD from an obligate anaerobic bacterium Desulfovibrio vulgaris[9]. Combined with the results of activity assays and metal content determination, this purified protein was an iron-containing SOD. The UV-visible spectra of the recombinant SOD are shown in Fig.2(b). The spectra are similar to those previously reported for Fe SOD proteins[9-10]. The maximum visible absorption of the protein was located at 350 nm, which was typical for proteins containing iron atom. The results further confirmed that the recombinant SOD protein was correctly folded and the Fe atom was also correctly inserted into the active site of the protein expressed in E. coli.

Fig.2 MALDI-TOF-MS (a) and UV-vis scanning (b) spectra of recombinant SOD protein from A. ferrooxidans Fe-1

3.5 Molecular structure modeling of SOD protein

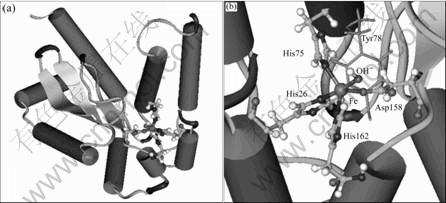

The results of search on PDB for the sequence of SOD from A. ferrooxidans showed that the crystal structure of a Fe-superoxide dismutase from the hyperthermophile Aquifex pyrophilus (PDB code 1COJ) [11] had the best sequence similarity (54.15%), so 1COJ was used to model the 3D structure of this protein. When the obtained structure is accessed by ProStat program, no significant differences of structure features in the modeled protein are observed. When the obtained structure is checked by Profile-3D program, the compatibility scores for each residue are all above zero, which corresponds to acceptable side chain environments. The above results from Profile-3D and ProStat programs indicate that the modeled structure is reliable.

The monomer of modeled SOD from A. ferrooxidans consists of 205 amino acids, with a relative molecular mass of 23.02×103 by calculation. It can be subdivided into two domains, an α N-terminal domain and an α/β C-terminal domain, connected by a loop (Fig.3(a)). There is a Fe binding site in the structure of the enzyme, in which iron is liganded by His26, His75, Asp158, His162 and a solvent water molecule with distorted trigonal bipyramidal geometry (Fig.3(b)). The Tyr78 is near Fe atom.

Fig.3 Modeled structure of SOD from A. ferrooxidans: (a) Overall structure; (b) Iron binding center

Till now, four evolutionarily distinct families of SODs are known, of which the Fe-binding family is one [7]. These geometric features of the modeled structure are well consistent with those of the general iron-depending SODs[11-13]. So the gene sod in A. ferrooxidans encodes Fe-SOD based on the modeled structure, in which the liganded iron absorbs superoxide radical. These results are obviously in line with the above experimental results.

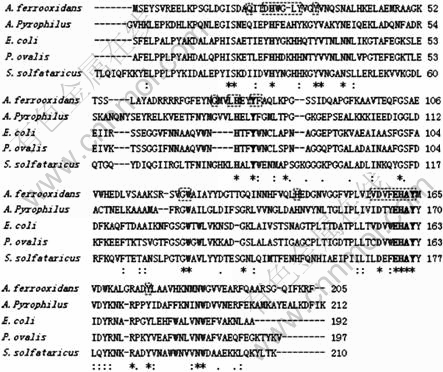

Sequences alignment of SODs from A. ferrooxidans and other sources also highlights the results of experiment and modeled structure (Fig.4). The sequences of SOD from A. ferrooxidans are 34%, 24%, 20% and26% identical to the Fe-SODs from A. pyrophilus, E. coli, P. ovalis and S. solfataricus, respectively. The residues of His26, His75, Asp158, His162 are highly conserved, and their important function for direct binding between iron atom and their counterparts in iron-SOD from other species have also been clearly studied[11-12]. The residues of Tyr78, Glu161, Ala163 and Tyr164 are also highly conserved, which were reported as fingerprints of Fe-SOD[13]. Especially, Tyr78 is one of the characteristic residues and proposed to be sensitive to hydrogen peroxide, which distinguishes Fe-SOD from Mn-SOD, while its counterpart in Mn-SOD is a phenylalanine[12-13]. Moreover, most of the residues around 8 ? from the binding iron atom in the modelling structure are conserved and form a site characterized by an unusually low rate of mutation. Such spatial site is sure to identify evolutionarily privileged functional site. Obviously in this work, this site is the active site candidate directly for catalytic function and iron binding.

Fig.4 Sequences alignment of Fe-SODs from A. ferrooxidans and other sources

4 Conclusions

The expression in E. coli of His-tagged SOD protein from A. ferrooxidans was reported. All the probed properties of the recombinant protein support that the protein was an iron-containing SOD and the iron atom was incorporated in the active site of the protein. Molecular modeling for the protein revealed that the iron atom was in ligation with His26, His75, Asp158 and His162. The Tyr78 sensitive to hydrogen peroxide was near the iron atom.

References

[1] FRIDOVICH I. Superoxide radical and superoxide dismutases [J]. Annual Review of Biochemistry, 1995, 64: 97-112.

[2] BANNISTER J V, BANNISTER W H, ROTILIO G. Aspects of the structure, function, and applications of superoxide dismutase [J]. CRC Critical Reviews in Biochemistry, 1987, 22: 111-180.

[3] JOHNSON F, GIULIVI C. Superoxide dismutases and their impact upon human health [J]. Molecular Aspects of Medicine, 2005, 26: 340-352.

[4] PARVATIYAR K, ALSABBAGH E M, OCHSNER U A, MICHELLE A. Global analysis of cellular factors and responses involved in Pseudomonas aeruginosa resistance to arsenite [J]. Journal of Bacteriology, 2005, 187: 4853-4864.

[5] GESLIN C,LLANOS J,PRIEUR D,JEANTHON C. The manganese and iron superoxide dismutases protect Escherichia coli from heavy metal toxicity [J]. Research in Microbiology, 2001, 152: 901-905.

[6] SCHMIDT A, SCHMIDT A, HAFERBURG G, KOTHE E. Superoxide dismutases of heavy metal resistant streptomycetes [J]. Journal of Basic Microbiology, 2006, 47: 56-62.

[7] FINK R C, SCANDALIOS J G. Molecular evolution and structure-function relationships of the superoxide dismutase gene families in angiosperms and their relationship to other eukaryotic and prokaryotic superoxide dismutases [J]. Archives of Biochemistry and Biophysics, 2002, 399: 19-36.

[8] HE Y Z, FAN K Q, JIA C J, WANG Z J, PAN W B. Characterization of a hyperthermostable Fe-superoxide dismutase from hot spring [J]. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol, 2007, 75: 367-376.

[9] NAKANISHI T, INOUE H, KITAMURA M. Cloning and expression of the superoxide dismutase gene from the obligate anaerobic bacterium Desulfovibrio vulgaris (Miyazaki F) [J]. J Biochem, 2003, 133: 387-393.

[10] FREDERICK J, YOST J, FRIDOVICH I. An iron-containing superoxide dismutase from Escherichia coli [J]. J Biol Chem, 1973, 248: 4905-4908.

[11] LIM J H,YU Y G,HAN Y S,CHO S J, AHN B Y, KIM S H, CHO Y. The crystal structure of a Fe-superoxide dismutase from the hyperthermophile Aquifex pyrophilus at 1.9 ? Resolution: Structural basis for thermostability [J]. Journal of Molecular Biology, 1997, 270: 259-274.

[12] URSBY T,ADINOLFI B S,AL-KARADAGHI S,DE V E, BOCCHINI V.  Iron superoxide dismutase from the archaeon Sulfolobus solfataricus: Analysis of structure and thermostability [J].

Iron superoxide dismutase from the archaeon Sulfolobus solfataricus: Analysis of structure and thermostability [J].  J Mol Biol, 1999,

J Mol Biol, 1999,  286: 189-205.

286: 189-205.

[13] PARKER M W, BLAKE C C. Iron- and manganese-containing superoxide dismutases can be distinguished by analysis of their primary structures [J]. FEBS Letters, 1988, 229: 377-382.

[14] BAKER B J, BANFIELD J F. Microbial communities in acid mine drainage [J]. FEMS Microbiology Ecology, 2003, 44: 139-152.

[15] QUATRINI R, APPIA-AYME C, DENIS Y, JORGE V, SILVER S. Insights into the iron and sulfur energetic metabolism of Acidithiobacillus ferrooxidans by microarray transcriptome profiling [J]. Hydrometallurgy, 2006, 83:263-272.

[16] RAWLINGS D E, KUSANO T. Molecular genetics of Thiobacillus ferrooxidans [J]. Microbiological Reviews, 1994, 58: 39-55.

[17] BRADFORD M M. A rapid and sensitive method for the quantitation of microgram quantities of protein utilizing the principle of protein-dye binding [J]. Anal Biochem, 1976, 72: 248-254.

[18] LAEMMLI U. Cleavage of structural proteins during the assembly of the head of bacteriophage T4 [J]. Nature, 1970, 227: 680-685.

[19] McCORD J M, FRIDOVICH I. Superoxide dismutase: An enzymic function for erythrocuprein (hemocuprein) [J]. J Biol Chem, 1969, 244: 6049-6055.

[20] BEAUCHAMP C, FRIDOVICH I. Superoxide dismutase: Improved assays and an assay applicable to acrylamide gels [J]. Anal Biochem, 1971, 44: 276-287.

[21] CLARE D A, BLUM J, FRIDOVICH I. A hybrid superoxide dismutase containing both functional iron and manganese [J]. J Biol Chem, 1984, 259: 5932-5936.

Foundation item: Project(2004CB619201) supported by the National Basic Research Program of China; Project(50621063) supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China

Corresponding authors: QIU Guan-zhou, LIU Xue-duan; Tel/Fax: +86-731-8879815; E-mail: lydcsu@yahoo.com.cn, xueduanliu@yahoo.com.cn

(Edited by YANG Bing)